An ample and engaged workforce is fundamental to economic growth and rising standards of living. At a personal level, work provides an innate sense of dignity and purpose, and a shared work ethic helps to build communities and foster a sense of belonging. In short, work is a fundamental component of human flourishing.

An evolving economy and changing cultural norms have created opportunities for many workers, but also losses and struggles for others. While real median earnings in the U.S. are higher today[1] than ever before, some workers lack opportunities to get ahead, some feel left behind, others lack motivation, and many families find it hard to achieve their goals. There is no cure-all solution to what is lacking in America’s labor market and among its workforce, and there is significant contention over the best ways to help more workers thrive.

To address real and perceived worker struggles, liberals tend to call for greater government intervention and increased unionization while traditional conservatives emphasize the effectiveness of free markets and the importance of personal freedom to maximize opportunities and generate rising incomes. And a new group of capitalism-skeptical “conservatives” seek conservative social outcomes through economically liberal means.

This paper will consider the role of unions compared to other policies to expand opportunities and prosperity for American workers and families.

Overview of the American Labor Market

By many metrics, America’s labor market is strong; unemployment is relatively low and job openings are high. But total incomes and economic growth are held back by a decline in labor force participation. The percentage of the U.S. population ages 16 and over who are working is 4.8 percentage points lower today than at the turn of the 21st century. Much of the decline in employment is concentrated among young men, including a 7.8 percentage point decline in the employment-to-population ratio of men ages 35 and younger, which translates into 3.2 million fewer young men working today.[2] Some of the factors contributing to declines in employment include physical and mental health,[3] substance abuse and addiction,[4] increased government transfers,[5] and cultural shifts.[6]

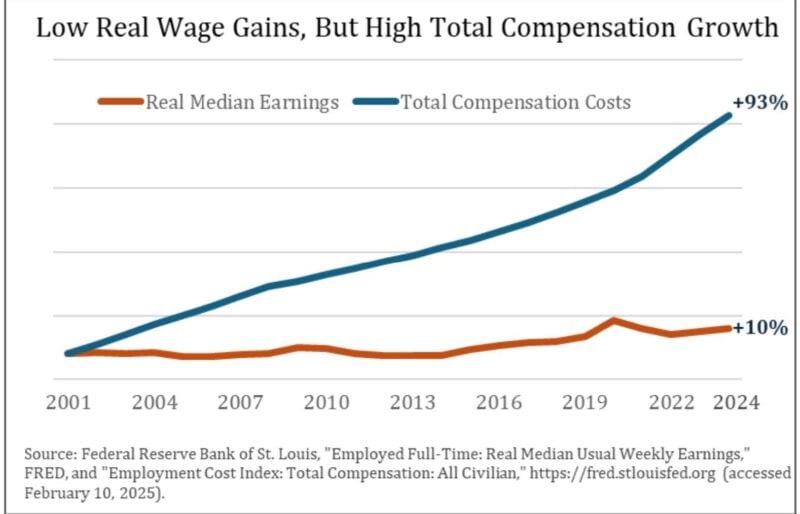

The recent period of low unemployment has failed to produce the same sustained real income gains as in the 1950s, in part because rising health care costs and other increased worker benefits have reduced real wage gains. Whereas real median weekly earnings increased only 10 percent between 2001 and 2024, total compensation, as measured by the employment cost index, increased 93 percent.[7]

Foundation of Mid-20th Century Worker Power was Built on Unstable Ground

Lackluster wage gains over much of recent decades have caused many to yearn for the apparent worker heyday of the mid-20th century, with strong income growth, high unionization, and the ability for a typical male breadwinner to support a middle-class family. But those seeming glory days of worker power were artificially inflated by unsustainable union compensation, real sex- and race-based discrimination, the confines of a non-global economy, and amid very different cultural norms.

For starters, many “good union jobs” were simply not sustainable. Above-market compensation and union-imposed operational constraints limited many companies’ ability to adapt to increased globalization and the shift away from manufacturing and towards services. While U.S. manufacturing output continued to increase even as many manufacturing employers failed, some of those employment losses and resulting longer-term shifts in U.S. manufacturing might have been avoided if companies had been free to adapt.[8]

Another common lament related to workers’ compensation is the loss of workplace pensions most often provided by unionized jobs. Yet, many of the generous union pensions and retiree health benefits that were so valuable to early generations of workers now function more like Ponzi schemes than secure pensions.[9] As of 2020 and prior to taxpayer bailouts, private union, or multiemployer pension plans had promised an estimated $823 billion more in benefits than they set aside to pay,[10] and were on track to pay only 41 cents on the dollar of promised benefits. This is not the result of just a few bad plans; 96 percent of the roughly 11 million unionized workers and retirees with multiemployer pensions are in plans that are less than 60 percent funded.[11] Without taxpayer bailouts—which are currently limited to about 15 percent of union pension plans—nearly all workers and retirees with private union pensions would receive less than half of their promised benefits.[12]

Moreover, relatively high median wage growth in the middle of the 20th century was propped up by New Deal policies that elevated some workers’ wages at the expense of other workers’ jobs, government intervention in production during World War II, and very real employment discrimination against women and minorities prior to passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A 2024 report from Scott Winship at the American Enterprise Institute, “Understanding Trends in Worker Pay over the Past 50 Years,” notes that oft-cited statistics of low or no wage growth are based on selective, noncomprehensive metrics, and are typically tied to an “unanchored” period in which pay exceeded productivity for multiple reasons.[13] In reality, total worker compensation has closely tracked total productivity, and compensation differences across industries and firms also correspond to differences in productivity.[14]

While economy-wide compensation and productivity closely align, Winship notes that women have experienced significantly higher compensation growth, with their real median hourly compensation increasing 69 percent between 1973 and 2022, compared to a gain of just 16 percent among men.[15] As Winship writes, “Men used to live in a world where their pay got a boost from patriarchal norms; where they dominated higher-productivity, higher-paying jobs; and where they faced little competition from female labor. The transition from that world was painful for many men.”[16]

While the good news is that both men and women have experienced real productivity and compensation gains since the mid-1990s and their wages are decidedly higher than in the past, workers’ incomes are still not what they could be and should be.

Can A Labor Union Revival Increase Worker Prosperity?

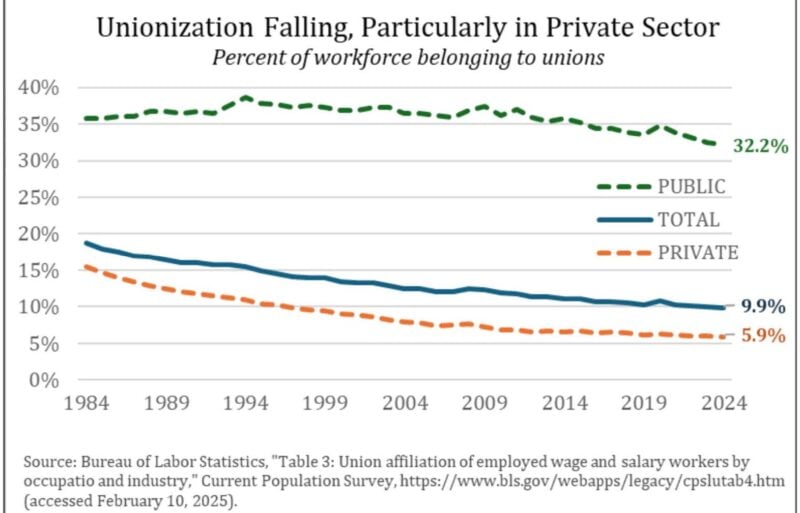

Labor unions have played an important role in U.S. history. Particularly during the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century, unions helped workers gain safety and health protections, secure reasonable wages, and provided them with a previously unheard-of voice in management. Today, labor laws and a globally competitive economy have largely replaced unions’ traditional value. Yet, many unions have maintained the industrial-era union model that provides less value to the increasingly educated, transient, and adaptable workforce. The shift away from lower- to higher-skilled manufacturing jobs[17] and more service-oriented jobs[18] has rendered unions’ one-size-fits-all policies and pay scales ineffective and undesirable for many workers who want to be recognized for their unique contributions. Consequently, the unionization rate in the U.S. declined from a peak of 33.5 percent in 1954 to an all-time low of 9.9 percent in 2024, including only 5.9 percent unionization among private sector workers.[19]

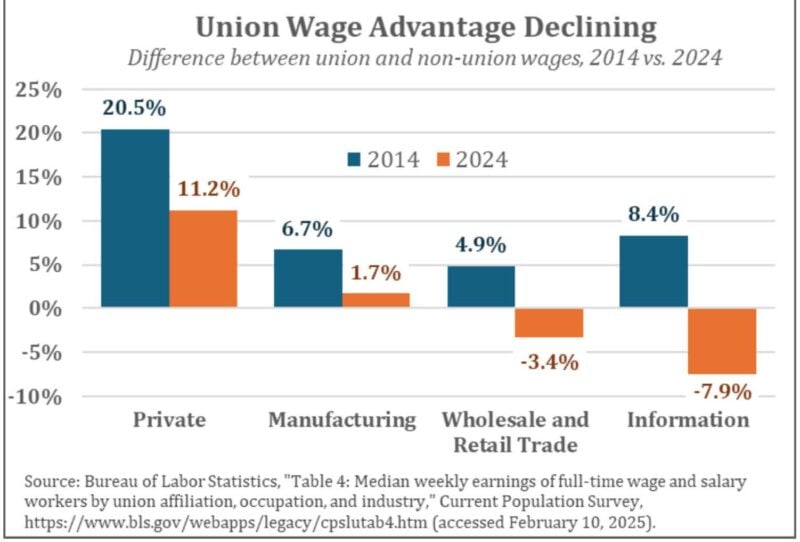

Historically, comparisons of all union jobs versus all non-union jobs show that union jobs pay more than non-union jobs.[20] That wage premium has declined sharply in recent years. Whereas union jobs paid 27.1 percent more than non-union jobs in 2014, they paid just 17.5 percent more in 2024.[21] Among private-sector jobs, the union wage premium fell by nearly half, from 20.5 percent in 2014 to 11.2 percent in 2024.[22]

A better apples-to-apples comparison of jobs within the same industry shows that unions’ wage advantage has declined in nearly every industry over the past decade.[23] In manufacturing, the wage premium is just 1.7 percent, and in wholesale and retail trade, union workers now make 3.4 percent less than non-union workers. This does not include the additional one to two percent of workers’ wages that unions take as fees out of workers’ paychecks.

These relative wage declines have occurred even as, or perhaps because unions—predominantly national, Big Labor organizations—have increased their efforts to use politics and power to gain union members. By diverting more of workers’ dues to national organizations and focusing more on national causes that are of little, no, or negative value to many unionized workers (such as social and political causes, minimum wages and benefits that unionized workers already have, or changes in the law to make it easier to unionize and harder to get rid of unwanted unions), Big Labor has arguably detracted from what could be the positive effects of local unions working alongside employers to help workers achieve long-term wage gains.

What Do Labor Unions Do?

Unions’ stated purpose is to represent and protect workers’ rights and interests in the workplace. Due to exclusive representation laws, this requires unions to represent an entire group of workers who may have differing interests and desires.

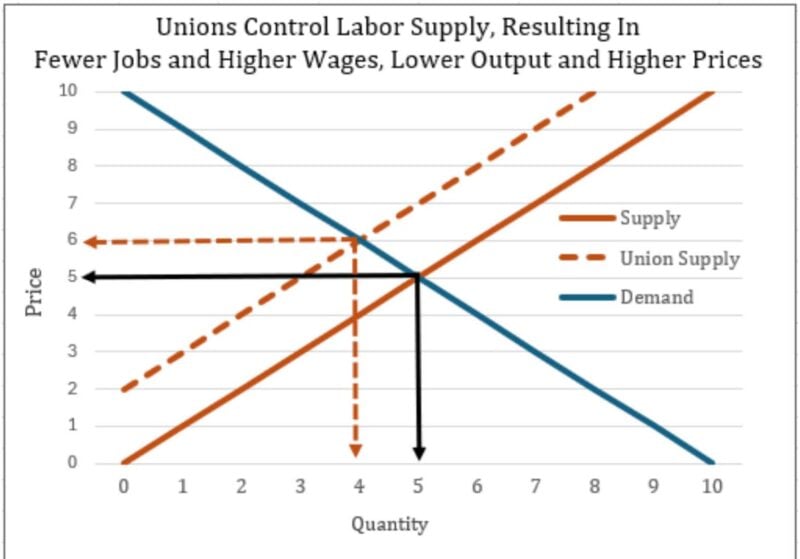

In practice, unions’ primary purpose is to control the workplace, including controlling the supply of workers and controlling all operations related to workers, both of which typically increase employers’ costs and constrain their operations.[24]

Unions control workers and limit the supply of workers.

Due to exclusive representation laws, all workers within a unionized workplace must be represented by the union and cannot negotiate with their employer on their own behalf. Combined with an exceptionally difficult process to get rid of an unwanted union, unions have substantial control over workers.

One of the first laws of economics is that when the cost of something increases, demand for it decreases. Unions drive up labor costs for employers by demanding above-market compensation and imposing rigid workplace rules, and because employers cannot hire workers outside of the union contract, this results in fewer union jobs. Higher labor costs also typically translate into higher prices for the goods and services that workers produce, which also reduces demand for those goods and services. The balance of economic analysis across all industries finds that unions reduce employment by five to ten percent at newly organized companies.[25]

By controlling the supply of workers to manipulate workers’ compensation, unions function like cartels. While it is illegal for companies to form cartels, it is not illegal for unions to form labor cartels. As James Sherk explained in “What Do Unions Do: How Labor Unions Affect Jobs and the Economy,” the government would prosecute Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler if they colluded to standardize automobile production and increase automobile prices, but union officials who organize and represent the workers of Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors can collude to standardize automobile production and increase autoworkers’ compensation—both of which affect automobile prices.[26]

This is what autoworkers did through the United Auto Workers (UAW) union in America. For decades, this worked to the benefit of more than one million U.S. autoworkers because, when the only cars Americans could buy were those produced in the United States by UAW members, the union could impose above-market compensation and impede production efficiencies without the threat of competition. But less efficient production and higher costs meant slower advancement in automobile quality and safety, higher prices and fewer people able to afford cars, and fewer workers needed to produce them.

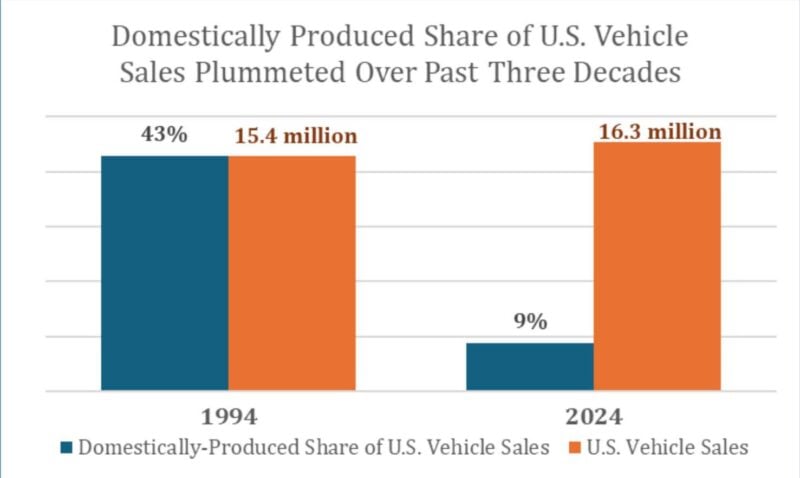

When foreign competition entered the market and the UAW prevented the industry from adapting, U.S. auto production and unionized autoworker jobs fell.[27] Domestic auto production today is only 20 percent of what it was three decades ago. And even as total vehicle sales in the U.S. have increased about 8 percent, the domestically produced share of total vehicle sales fell from 44 percent in 1994 to 9 percent in 2024.[28] Were it not for a taxpayer bailout of the auto industry (in particular, of UAW pensions), the number of shuttered auto manufacturing plants and lost union autoworker jobs would be even greater.[29]

Even today, the UAW continues to limit the supply of jobs on both the front and back end. For starters, it can be hard to get union jobs. Sara Schambers, a “proud fourth-generation Ford autoworker” and current UAW member explained in testimony at a 2024 U.S. Senate hearing that she has been an autoworker for 17 years but had to spend the first six years as a temporary worker before being hired as a permanent worker with full union benefits.[30] And union provisions that prevent profitability lead to job losses. Within less than a year of the UAW strike that resulted in significant compensation increases, the Big Three automakers laid off thousands of workers.

Unions replace individual voices and direct relationships with a collective voice and exclusive representation.

When a workplace becomes unionized, it severs the direct relationship between workers and management. Instead of workers negotiating their compensation, schedule, and job duties with a manager, and their raises and promotions being determined based on their performance, the union single-handedly negotiates the pay and promotion scales, the benefits packages, the schedule rules, and job duties for all workers.

Unions prevent merit-based pay.

Unions typically replace merit-based pay and promotions with seniority-based determinations. While this system works well for workers with longer tenure, it can unjustly penalize newer, industrious workers, as well as those with priorities that differ from the union’s, such as a parent who wants or needs a part-time schedule.

This was the case for two dozen hardworking employees at Giant Eagle grocery store in Edinboro, Pennsylvania who had their raises revoked by the union that represented them. The union opposed the raises because the employer—not the union—decided to give them to the workers. Although the union won its case because its contract gave the union control over workers’ wages, the Judge noted that the union’s actions were “causing harm to its own members.”[31]

Preventing merit-based pay hurts far more people than it helps, including entire companies’ success. That is because economic studies find that merit-based pay increases productivity by six to 10 percent, and productivity is what drives wage growth.[32]

Unions intervene in daily operations.

Unionization can feel like a hostile takeover because a union’s intervention into everything workforce-related can significantly alter a company’s operations. In many unionized workplaces, union officials have more control over the company’s day-to-day operations than the owner and managers.[33] Many of unions’ dictates are tedious and their constant oversight can prevent managers from achieving productive and positive workplaces.[34]

For example, a former manager of a unionized workplace told of one instance in which he picked up a zip tie from the floor that one of his employees had dropped from the platform above. The union representative who was monitoring the floor wrote him up for taking work away from a unionized employee. That harmless violation of the union contract later served as leverage for the union to get a worker reinstated after she was fired for being intoxicated at work and injuring a manager while operating heavy machinery.

Unions create adversarial relationships.

Employers and employees are naturally in business with one another—not against one another. If a company does well, it can increase wages and add jobs; if a company does poorly, it will have to reduce wages and cut jobs. Yet, unions thrive on adversarial relationships and strong-arm tactics that pit workers and employers against one another. Once a workplace is organized, workers are prohibited from communicating directly with their managers regarding things like suggestions, concerns, or personal requests, and workers are generally taught to view management as the enemy. That includes union campaigns’ dehumanizing strategy of using a 10-foot inflatable rat to depict management and anyone else who does not toe the union line.[35] This is destructive to workers’ and employers’ shared success and creates hostile and disrespectful workplaces.

Unions reduce investment, modernization, and growth.

Unions often prioritize short-term, tangible gains over investments that lead to long-term success and wage gains. Studies find that unionization causes companies to reduce investment by roughly 10 percent to 30 percent.[36] One study that examined firms’ investment before and after unionization found that the reduced investment effect of unionization was equivalent to a 33-percentage point increase in the corporate tax.[37]

One example of unions’ short-sighted protectionism comes from the International Longshoremen’s Association union, with its president claiming that automation is an existential threat to union members and maritime employees.[38] At California’s ports, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union have successfully fought against automation in an attempt to protect their unionized workers jobs, which average $233,000 of earnings per year.[39] This fight against progress is based on the mistaken notion that automation will reduce jobs at ports, but a 2022 study commissioned by the Pacific Maritime Association concluded that, “Increasing automation will enable the largest West Coast ports to remain competitive, facilitate both cargo and job growth, and reduce greenhouse-gas emissions to meet stringent local environmental standards.”[40]

The ILWU responded by noting that while ports that automated increased jobs, some of those jobs came at the expense of nearby ports that did not automate. That is precisely the case in point. Companies will ship to the ports that are the most efficient—even if that means longer shipping routes. California’s two largest ports ranked among the lowest in the world, with Los Angeles at number 336 and Long Beach at number 346 out of 348 in total, and the efficiency report noted that the California port scores were propped up by the fact that some deliveries that would have been unloaded there waited so long that they were rerouted and thus some of the least-efficient deliveries were not ever included in the ports’ records.[41]

While we cannot comprehend the positive benefits of automation that has not yet occurred, just imagine if the implementation of automated tolls had been blocked to protect the jobs of toll-booth operators. Not only would Americans be spending hundreds of thousands more hours per year idling in traffic, but all of those better-paying, automated toll system jobs inside climate-controlled offices would not exist.

Technology makes workers more productive, and automation creates as many or more jobs as it eliminates, while also reducing prices and saving time for consumers across the economy. Companies that fail to innovate will lose out to those that do, and unions that oppose automation will lose more jobs than they save.

Unions hinder flexibility and responsiveness.

Union contracts typically span a minimum of three years. These contracts lock employers into a rigid cost structure and inflexible operations. Those restrictions were particularly harmful during the COVID-19 pandemic as companies had to respond to forced closures, implement new safety procedures, enable remote work capabilities, and alter their operations.

Non-unionized companies could communicate with and respond to their employees’ concerns and needs. For example, the then non-unionized Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga Tennessee sent workers text messages asking them about how they were feeling about proposed return to work plans and providing the opportunity for them to respond to specific questions. And while private schools with non-unionized teachers quickly implemented new safety measures and reopened, teachers’ unions pressured public schools to remain closed—which many did for more than a year, to the detriment of potentially lifelong consequences for their students.

Union restrictions also made it harder for companies to respond to increased demand and worker shortages. In 2022, American Airlines tried to address its pilot shortage by offering current pilots an opportunity to earn additional money, on their days off, by participating in the training of new pilots. The pilots’ union sued American Airlines because the union contract did not specify that it could offer additional hours and income. The result: fewer jobs for pilots and supporting airline staff, more disruptions and higher costs for travelers, and likely more demanding flight routes for pilots.

The multi-year contract structure of unions also prevented unionized workplaces from responding to rising compensation trends. Between 2019 and 2024, non-unionized workers’ pay increased 5.8 percentage points more than unionized workers’ pay (non-unionized pay increased 27.6 percent, compared to 22 percent for unionized workers).[42]

Would Greater Unionization Increase Workers’ Prosperity?

President Lincoln famously stated, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” This goes for workplaces as well. Workers and employers are in competition together, but unions often upend that natural relationship and pit workers and employers in competition against one another. Instead of focusing on ways that collective worker organization can help workers and employers—like training workers in new technologies, and incentivizing productivity through performance-based bonuses—unions often focus on dictating the operations of businesses and the compensation of workers. This is increasingly true of national, Big Labor organizations that seem more focused on lobbying politicians to change the laws to make it easier for unions to extract dues from more workers’ paychecks than on delivering meaningful value so that more workers willingly join and pay union dues.

Unions specialize in representing workers, not running businesses.

Top-down, command-economies always produce inferior results because bureaucrats and politicians cannot set output and prices better than the people who make and consume those products. Similarly, union officials cannot understand business operations better than the people who built their businesses, and union officials cannot understand any one worker’s circumstances and preferences better than the worker himself. Thus, union intervention typically increases costs and creates inefficiencies.[43] A study that examined the impact of unionization on stock market prices estimated that unionization caused a 10 percent to 14 percent decline in company value.[44] Declining values generally lead to fewer jobs and lower worker compensation in the long-run.

Super-sized sectoral bargaining would restrict American ingenuity and productivity.

Sectoral bargaining is a form of super-sized unionization whereby a union controls the wages and working conditions across an entire industry, such as trucking or auto manufacturing, instead of within one company.[45] For example, if the U.S. imposed sectoral bargaining across the entire auto industry, all non-unionized car manufacturers would have to follow complex and rigid union compensation scales and workplace rules. This would upend the way they do business, almost certainly causing some to go out of business entirely and causing those who stay in business to raise prices and likely scale back production.[46] The inability of employers to use higher compensation to incentivize innovation and reward productivity would result in less of both. Moreover, sectoral bargaining would create a barrier to entry for new companies. All businesses start out small and typically cannot pay their workers as much as bigger businesses until they become bigger businesses themselves. But if they are not allowed to pay lower wages when they first start out, they will not start at all. Sectoral bargaining would also limit workers’ ability to improve their compensation and career trajectories by taking a new job with a competitor (because compensation would be uniform throughout the sector). In short, sectoral bargaining would suppress competition and stifle innovation, which would hurt workers and consumers alike.

Unions actively drive out small businesses and independent workers.

Unions’ profitability is directly related to businesses’ size, which is why union organizers typically target big corporations that employ hundreds or thousands of workers. In an effort to force more workers into big business jobs, Big Labor has been using its money and political power to try to outlaw small business models and independent contractor jobs that cannot be easily unionized.[47],[48]

Big Labor’s assault on independent contractors threatens more than 60 million Americans who perform independent work, as well as small businesses that disproportionately rely on independent contractors to compete with big businesses.[49] A California law limiting independent contracting, which is similar to what the Biden-Harris Administration imposed in 2024,[50] was estimated to reduce self-employment by 10.5 percent and total employment by 4.4 percent.[51]

Government actions to tip scales in favor of unions have consequences for workers.

Historically, while unions work to extract as much as they can out of companies, they have often been willing to make concessions to avoid bankruptcy. Now that the federal government has forced taxpayers to bail out the unionized auto industry,[52] forced taxpayers to bail out failed union pensions,[53] and the Biden-Harris Administration pursued a “Whole of Government” approach to increasing unionization,[54] the strategy of unions—in particular, the “Big Labor” movement—may be changing to the detriment of individual workers.

Whereas a single, unaffiliated local labor union representing workers at one company necessarily will focus on the needs and desires of its workers, National Big Labor unions that represent workers across many industries and employers increasingly focus on obtaining money and political power and are sometimes willing to sacrifice the wellbeing and livelihoods of their own members if it expands their influence.

In 2012, new owners of the beleaguered Hostess Brands were trying to prevent the company from bankruptcy. One of the company’s challenges was significantly higher labor costs than its competitors. In exchange for wage and pension cuts, the owners offered workers a 25 percent ownership stake in the business and representation on the board. But the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers, and Grain Millers International Union refused the offer and ordered its workers to strike. Despite Hostess revealing its books warning that the strike would bankrupt the company, the union continued the strike. Hostess filed for bankruptcy and more than 18,000 Hostess employees lost their jobs.

In 2023, another struggling company, Yellow Trucking, was trying to turn things around with a modernization plan it had already successfully implemented in its west-coast operations. One of the efficiencies included in the plan required the union to sign off on allowing 600 utility truck drivers to sometimes perform dock work when they would otherwise have been idle on the clock. The Teamsters union objected to that and other changes and refused, for eight months, to negotiate with Yellow, claiming that it was too busy with its UPS negotiations. Without even presenting Yellow’s offer to truckers—which included a large pay increase—Teamsters’ President Sean O’Brien seemingly decided that after 99 years in operation, Yellow Trucking did not deserve to exist. Using his @TeamstersSOB account on “X,” O’Brien posted an image of a cemetery headstone with “Yellow 1924-2023” on it.[55] When questioned about his actions that cost 30,000 Yellow employees—including 22,000 union workers—their jobs, O’Brien said, “Sometimes a bad job isn’t worth it anymore.” Unfortunately, because exclusive representation requires those 22,000 unionized workers to allow a national union leader to speak on their behalf, they never had a say in whether or not their jobs were worth it anymore.

Instead of standing up for and representing workers, the actions of some national Big Labor union leaders are silencing the voices of tens of thousands of workers in exchange for personal power and influence.

If Not Big Labor, What Can Increase Worker Prosperity?

Labor unions played an important role, historically, in the U.S. by securing important health and safety protections. With unions’ original demands and countless additional labor regulations now codified in law, unions’ roles have shifted. While some unions continue to provide valuable services to workers—like education and training to keep pace with evolving technology and practices—most unions have failed to adapt and do not deliver services that workers believe are worth the dues that unions extract from their paychecks.

At the heart of worker prosperity is worker productivity. Renowned—and now 94-year old—economist Thomas Sowell was asked what advice he would give to young African Americans today on how to make something of themselves. Sowell’s response:

The way anybody else would—you equip yourself with skills people are willing to pay for.[56]

That simple directive, “equip yourself with skills people are willing to pay for,” is the crux of worker prosperity. No elite idea, government program, or union coercion can deliver worker prosperity; the only way for workers to achieve lasting income gains is by becoming more productive. And the only way that workers can become more productive is through education, experience, and access to capital—like equipment and technology—that increases their capabilities.

While many workers feel like they have been left behind, are struggling to get ahead, or that they lack a meaningful voice in the workplace, there is tremendous potential for a brighter, more prosperous future. Better labor organizations rooted in worker freedom, alongside a reduction in government-imposed barriers to education, employment, and rising incomes can enable more Americans to flourish.

Alternative, Voluntary Labor Organizations

There is strength in numbers and workers can benefit by banding together to achieve their shared goals. There is also strength in unity, and workers and employers can achieve more when they are working directly together towards shared success than when they are pit against one another by a middleman.

So how can workers and employers have more communications with, and investment in one another? The solution is voluntary engagement, absent the strong arm of unions. Workers should never be forced to pay for services they do not desire, nor should they be prevented from choosing their own representation or negotiating on their own behalf with their employer. Likewise, employers should not have to succumb to micromanagement by an outside organization to meet worker desires.

The following models offer ways to improve upon employee and employer relations, for workers’ voices to be heard, and for both workers and employers to grow and succeed:

Worker-choice arrangements.[57]

The union exclusivity model is flawed for workers and unions alike. It forces workers in unionized workplaces to give up their rights to negotiate directly with their employers and forces them to accept the union’s representation. This is especially problematic because 95 percent of union members never voted for the union that represents them.[58]

Meanwhile, exclusive representation poses a free-rider problem for unions that have to represent all workers even if they choose not to join and pay the union.[59] States, on behalf of their public employees, and Congress, on behalf of private-sector workers, could free unions from the so-called free rider problem by enacting worker-choice models where unions still bargain collectively, but only on behalf of the members they represent.[60] Workers who want the benefits of the union would have to pay union dues, and those who do not could choose their own representation. Unions could even allow workers to pick and choose the services they want to contract with the union to receive.

Professional worker organizations.[61]

Workers do not have to be employed by the same company or even in the same field of work to unite around common interests and pool resources to secure benefits or to share best practices. The Association of Independent Doctors is a professional organization that gives independent doctors who previously lacked organization and combined power a collective voice and the ability to pool together to obtain lower-cost health insurance. Another organization, the dues-free Freelancers Union has attracted nearly half a million workers across very diverse professions and wide income ranges by providing things that workers value, such as education, insurance benefits, and advocacy for their rights and interests. An advantage of professional organizations is that workers can take their benefits with them from one job, contract, or gig to another.

Education and certification.

As technology and trade continue to alter the workplace, unions or worker associations could provide valuable education and voluntary certifications to help prepare workers for changes within their own career or help them to gain the skills and experience for a new type of work. Some unions do provide valuable worker training, which could be expanded by linking up with other, non-unionized companies and education programs to expand workers’ access to opportunities. This would be particularly beneficial for workers in declining industries who could learn new skills to increase their income opportunities and reduce their risks of unemployment.

Certifications from worker or industry organizations can also improve workers’ job options by serving as a trusted measure of knowledge and experience. If coupled with the removal of unnecessary occupational licensing standards, optional certifications could increase job opportunities and incomes by providing effective signals of workers’ capabilities without blocking entry to employment for non-credentialed individuals.

Representation services.

Unions tend to focus most on workers’ wages and benefits, but the typical seniority-based structure that unions impose is not well-suited for the increasingly diverse range of positions, skills, and expertise at many workplaces. Moreover, as the workforce is increasingly mobile, the defined benefit pensions that make up a significant portion or union-negotiated compensation are of little or no value to many workers who do not stay in a job long enough to become vested in a pension system.

To remain relevant to a more varied and mobile workforce, unions could provide more narrow services, such as setting minimum salary requirements while still allowing individually-negotiated compensation. This is the type of structure that the Major League Baseball Players Association provides, for instance.

Reducing Government Barriers to Worker Prosperity

Work is essential for life and for well-functioning societies; thus, governments have a role in supporting work. Not surprisingly, countries with the most work opportunities are the most productive, prosperous, and free.

For a variety of reasons, including both individual and societal, not everyone has equal work opportunities. There are no cure-all solutions to these inequities, and there is significant contention over the best ways that society or governments can improve work opportunities and outcomes, including whether government intervention is necessary at all. Historically, countries in which lawmakers seek to micromanage the economy and labor market have produced worse outcomes for workers’ well-being and freedom; for example, the centrally planned economies of Cold War–era Eastern Europe had significant underutilization of resources and 38 percent lower GDP per worker than the predominantly market economies of Western Europe, and they ultimately failed.[62]

While the U.S. has a predominantly market economy, government policies still restrict workers’ opportunities across all walks of life—from limited primary education options[63] to excessive and skewed higher education subsidies, detrimental labor laws, personal rights restrictions, and excessive taxes on workers and employers.[64] These interventions create barriers to workers becoming more productive, and increased productivity is the only lasting way for workers to become more prosperous.[65]

The following policies would help enable rising incomes, expand work opportunities, and support human flourishing.

Make work pay.

The government’s current tax and redistribution structure tips the scales away from work and towards welfare. In 2024, the federal government spent $3.6 trillion in transfer payments, representing over $27,000 per household and nearly $3 out of every $4 the government collected.[66] High amounts of transfer payments make it easier for people to not work and they also require high levels of taxes on workers, which reduces the return to work. By reducing transfers and taxes, policymakers would make work pay more and not working pay less. When work pays more and not working pays less, people will tend to work more and consume less in government transfers.[67]

Review and eliminate unnecessary occupational licensure laws.

In theory, licensure laws protect the public from unqualified or unscrupulous practitioners. In practice, many state licensure schemes act as cartels that protect incumbents from competition.[68] Licensure laws are especially harmful to younger and lower-income individuals and the more than one in four American adults who have a criminal record.[69] Requiring people to pay hefty fees and attend dozens or hundreds of hours of training before they can legally become barbers, bartenders, ballroom dance instructors, florists, or hair braiders limits work and income opportunities and drives up costs for consumers. State policymakers should eliminate licensure laws that are not necessary to protect consumers and provide licensure reciprocity to make it easier for licensed professionals to move across state lines.[70]

Allow independent work options.

Increasingly, many Americans want or need more flexibility than a traditional nine-to-five job provides. And economic studies show that flexibility increases the number of people who can work, as well as the hours that people work and the incomes they earn.[71] More than half of the 64 million Americans who perform freelance work say that they are unable to work in a traditional job because of their personal health or their family caregiving needs.[72] A Biden Administration rule that took effect on March 11, 2024, could drastically restrict independent work opportunities.[73] A similar rule in California was estimated to reduce self-employment by 10.5 percent and total employment by 4.4 percent.[74] Congress should protect the right of individuals to work independently and eliminate regulatory flip-flopping by establishing a bright-line test, consistent across all federal laws, to determine who is an “employee” and who is an “independent contractor,” based primarily on how much control an employer exerts over a worker and with deference to workers’ preferred classifications in cases of ambiguity.[75]

Do not outlaw successful business models.

The franchise business model reduces barriers to entry for small business owners by providing a known brand along with a network of support and training for new franchise owners. It is increasingly attractive to minorities and women, who account for a rising share of franchise ownership. Without the franchise model, 39 percent of female franchise owners say they would not have been able to own their business.[76] Because it is not easy to unionize workers at each individually-owned franchise, unions have successfully lobbied government officials to push for a change in the definition of a “joint employer” to make it easier to unionize workers. Such a change would upend the franchise model.[77] Congress should codify a rational joint-employer definition based on the level of direct and immediate control an employer exercises.[78]

Expand apprenticeship programs by ending the government monopoly.

Apprenticeships are a proven alternative to degree programs, and a 2017 study estimated that the number of occupations commonly filled through apprenticeships could nearly triple, that the number of job openings filled through apprenticeships could expand eightfold, and that the occupations ripe for apprenticeship expansion could offer 20 percent higher wages than traditional apprenticeship occupations.[79] Yet, the Biden Administration cancelled new and expanding Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Programs, proposed an apprenticeship regulation that prohibits two of three existing Registered Apprenticeship Programs (which was abandoned at the end of its administration), and issued an executive order that will discourage companies from enacting their own, non-government-registered apprenticeship programs.[80] Congress should promote apprenticeship expansion across more industries.[81]

Reduce government spending.

The more that the government spends, the less that individuals can spend out of their own earnings. The surge in deficit-financed federal government spending since 2020 undoubtedly reduced labor force participation, fueled inflation, and resulted in real income losses.[82] Current federal government spending is unsustainable and it is mathematically impossible to simply tax the rich.[83] As Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute noted, “even 100% tax rates on million-dollar earners would not come close to balancing the budget, and seizing all $4.5 trillion of billionaire wealth—every home, car, business, and investment—would merely fund the federal government one time for nine months.”[84] Congress must immediately reverse recent spending explosions, and reform America’s entitlement programs so that current and future generations of workers do not have to surrender more than half of what they earn to finance their government.

Allow people to keep more of the income they generate.

When employees and employers can keep more of what they earn, they will work more and invest more, leading to more jobs and higher productivity. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) not only allowed workers to keep more of their earnings; it also enabled employers to make investments that led to more jobs and higher wages. A 2021 Heritage Foundation analysis found that the TCJA resulted in annual wages of more than $1,400 above trend.[85] The most efficient tax structure to maximize output and earnings is one that has a broad base (few exemptions and deductions), a low rate, and which does not double tax investments that boost productivity and wages.[86]

Eliminate Social Security’s retirement earnings test.

Social Security’s misunderstood earnings test is perceived by workers as an additional 50 percent tax on their earnings–leading to marginal tax rates as high as 84 percent–which causes people to work less, and thus earn less, than they otherwise would.[87] Policymakers should eliminate this outdated, paternalistic, and economically detrimental policy so that older Americans are not discouraged from working and earning more.

Reduce regulations to free up resources for more productive uses.

When entrepreneurs face fewer barriers to entry, they create more jobs. And when businesses do not have to comply with costly and unwarranted regulations, they have more resources to devote to raising wages, and educating and promoting workers. A forthcoming analysis by colleagues of mine at the Heritage Foundation and Economic Policy Innovation Center finds that a freeze in regulations for 10 years increases forecasted gross domestic product by 1.8 percent and also reduces the price level by an average of 0.6 percent per year and by 5.7 percent over 10 years. A reduction in the current level of regulation—such as President Trump’s “Unleash Prosperity Through Regulation” Executive Order that calls for identifying 10 regulations to eliminate for each new regulation issued—would have roughly twice as big of an impact on gross domestic product.[88] These positive impacts from reduced regulations translate into higher wages and greater purchasing power for workers.

Remove barriers to paid leave.

A flexible schedule and paid leave are valuable for virtually every worker; and for some workers, they are essential. Simply removing the federal government’s current prohibition against private employers offering their workers the choice between overtime pay and overtime “comp time”—something that many public-sector workers enjoy—would allow more lower-income and hourly workers to have the choice of accruing paid time off.[89]

Remove barriers to flexible work.

Many people want a little more flexibility in their schedule than a strict 9-to-5 job provides. Both the Obama and Biden Administrations attempted unsuccessfully to impose a drastic increase in the overtime threshold beyond which employers have to track salaried workers’ hours and pay them overtime—a move that would have caused employers to convert salaried workers to hourly workers with little or no flexibility or remote work options. Although those large increases were found unlawful, a future administration could pursue an increase that would inadvertently result in lost flexibility, lost benefits, less predictable paychecks, and lower total compensation.[90] Congress should amend the Fair Labor Standards Act to either: 1) clarify that it did not intend for the Department of Labor to create a salary threshold, or 2) specify what level of salary threshold it intends.

Allow accessible, affordable, and portable worker benefits.

The average worker will change jobs 12 times throughout his career, but no one wants to roll over his 401(k) plan or change health insurance 12 times. To expand portable benefit options, policymakers should equalize the tax treatment of employer-provided and privately-purchased benefits such as retirement savings and health and disability insurance. And to make it easier for all Americans to save for any purpose, policymakers should enact Roth-style Universal Savings Accounts.[91]

Enable better childcare options.

Childcare is critical for parents of young children who want or need to work, but it needs to be the type of care that parents want. Congress should remove an unintentional barrier in the Fair Labor Standards Act that makes it harder for businesses to offer childcare benefits,[92] should expand options for low-income families by making Head Start benefits portable,[93] and should enable more part-time and in-home care by creating a safe harbor for individuals who want to be independent contractors instead of household employees.[94] Additionally, state policymakers should remove unnecessary licensing requirements, which have contributed to a roughly 50 percent decline in the number of in-home childcare providers between 2005 and 2022.[95]

Protect union-members’ pensions.

Roughly 12 million workers and retirees belong to multiemployer, or union pension plans, that, as of 2020, had accumulated $823 billion in unfunded promises, and were on track to be able to pay only 41 cents on the dollar.[96] While a taxpayer bailout will temporarily prevent benefit cuts for about 15 percent of these workers and retirees, millions of workers and retirees stand to receive mere pennies on the dollar in promised benefits. Congress should protect union-members pensions by applying the same rules and regulations to union pensions as to non-union pensions.[97]

Prioritize workers’ choices about unionization.

Congress should prioritize workers’ choices and respect unions’ resourcesby simultaneously ending forced unionization and exclusive representation laws. This would allow more workers the option of joining a union and would eliminate unions’ “free rider” problem.[98]

Protect workers’ rights.

Recent regulatory actions and National Labor Relations Board decisions have trampled basic workers’ rights, including their privacy, their right to vote in a secret ballot election, and their protection from harassment. Lawmakers should ensure basic rights for workers, such as: requiring workers’ consent to use their union dues for political purposes; ensuring workers have access to a secret ballot union election; allowing individuals to opt out of having their personal information shared with union organizers; and allowing workers to receive raises or bonuses beyond what the union contract specifies.[99]

Conclusion

Even as the U.S. labor market is relatively strong, some workers have been left behind by economic and societal changes. It can be tempting to try to bring back what many view as the ideal labor market of the mid-20th century through government laws, and increased unionization. But unions’ chief tactics include limiting the supply of workers and impeding the production of goods and services, both of which reduce workers’ compensation and output in the long-run. Moreover, whereas small, local unions often work productively with management in ways that benefit workers, national Big Labor unions often put politics and power above the interests of workers they are supposed to represent.

Ultimately, legal constraints—whether through union contracts or government mandates—cannot make workers more productive or increase companies’ output. Instead of attempting to enact new laws and regulations, policymakers should eliminate existing government-imposed barriers to education, work, and rising incomes; and protect workers’ freedom to join a union or to not join a union and to instead represent themselves in the workplace. Similarly, unions should forgo tactics that have contributed to the decline of unionized industries and limited unionized jobs and instead focus on responding to workers’ desires and to employers’ needs in ways that lead to shared success.

Rachel Greszler is a Visiting Fellow in Workforce at the Economic Policy Innovation Center.

References

[1]Note: “today” is a general term for recent years as real median earnings peaked in 2020/2021, but this was artificially inflated by disproportionate job losses among lower-earning workers. See: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Real Median Earnings, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LES1252881600Q (accessed June 3, 2024).

[2]Author’s calculations based on employment and population data from: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, data through December 2024. In January 2000, the employment-to-population ratio of all people ages 16 and older was 67.3 percent, compared to an employment-to-population ratio of 62.5 percent in December 2024. In January 2000, the employment-to-population ratio of men under age 35 was 77.2 percent, compared to an employment-to-population ratio of 69.4 in December 2024.

[3]See, for example: Alan B. Krueger, “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry Into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, BPEA Conference Drafts, September 7 and 8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/kruegertextfa17bpea .pdf (accessed April 22, 2024), and Sneha Puri and Jack Malde, “Delving into the Reasons Why Some Prime-Age Men Are Out of Work,” Bipartisan Policy Center, February 29, 2024, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/why-some-prime-age-men-are-out-of-work/#:~:text=Fifty-seven%20percent%20of%20prime,emotional%2C%20or %20behavioral%20health%20reason (accessed April 26, 2024).

[4]See, for example: Ben Gitis and Isabel Soto, “The Labor Force and Output Consequences of the Opioid Crisis,” American Action Forum, March 27, 2018, https://www .americanactionforum.org/research/labor-force-output-consequences-opioid-crisis/ (accessed March 7, 2023); Ashley Abramson, “Substance Use During the Pandemic,” American Psychological Association Monitor on Psychology, Vol. 52, No. 2 (March 2021), https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/03/substance-use -pandemic#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Centers%20for,the%20onset%20of%20the%20pandemic (accessed March 7, 2023); and Jeremy Greenwood, Nezih Guner, and Karen Kopecky, “Did Substance Abuse During the Pandemic Reduce Labor Force Participation?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Policy Hub No. 5-2022, May 2022, https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/research/publications/policy-hub/2022/05/09 /05–did-substance-abuse-during-pandemic-reduce-labor-force-participation.pdf (accessed March 7, 2023).

[5]See, for example: Harry J. Holzer, R. Glen Hubbard, and Michael R. Strain, “Did Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Reduce Employment? Evidence from Early State-Level Expirations in June 2021,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 29575, December 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29575 (accessed February 5, 2022).

[6]Scott Winship, “Understanding Trends in Worker Pay Over the Past 50 Years,” American Enterprise Institute, May 2024, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Understanding-Trends-in-Worker-Pay.pdf?x85095 (accessed July 14, 2024).

[7]Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED Database, “Employment Cost Index: Total Compensation: All Civilian, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ECIALLCIV, and “Employed Full Time: Median Usual Weekly Real Earnings: Wage and Salary Workers: 16 Years and Over,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LES1252881600Q (accessed January 29, 2025). Data compares Q3 2024 to Q3 2001.

[8]Author’s calculations based on data from: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED Database, “Industrial Production: Manufacturing (NAICS),” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IPMAN; “All Employees, Manufacturing,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MANEMP; and “All Employees, Total Nonfarm” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS (accessed July 14, 2024).

[9]Rachel Greszler, “Not Your Grandfather’s Pension: Why Defined Benefit Pensions Are Failing,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3190, May 4, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017- 05/BG3190.pdf

[10]Table M-5, “PBGC-Insured Plan Participants (1980–2022),” and Table M-9, “Aggregate Funding of PBGC-Insured Plans (1980–2020),” Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, Multiemployer Program, Covered Plan Information Tables, https://www.pbgc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-pension-data-tables.pdf (accessed February 24, 2024).

[11]Table M-13, “Plans, Participants, and Funding of PBGC-Insured Plans by Funding Ratio (2020),” Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, Multiemployer Program, Covered Plan Information Tables, https://www.pbgc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-pension-data-tables.pdf (accessed February 24, 2024)

[12]Rachel Greszler, “What Taxpayers, Workers, and Retirees Need to Know About the Union Pension Bailout That Has Nothing to Do with COVID-19,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 6059, February 26, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/IB6059.pdf

[13]For example, such claims of unequal productivity and wage growth have: failed to include non-wage compensation, included only a subset of workers, and considered only the median worker’s wage compared to total productivity growth. Scott Winship, “Understanding Trends in Worker Pay Over the Past 50 Years.”

[14]Salim Furth, “Stagnant Wages: What the Data Show,” The Heritage Foundation, October 26, 2015, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/stagnant-wages-what-the-data-show (accessed January 29, 2025).

[15]Scott Winship, “Understanding Trends in Worker Pay Over the Past 50 Years.”

[16] Ibid.

[17]TERRA Staffing Group, “U.S. Manufacturing Growth and Outlook in 2020 and Beyond,” January 6, 2020, https://www.terrastaffinggroup.com/resources/blog/us-manufacturing-growth/ (accessed September 10, 2020).

[18]Between 1979 and 2019, manufacturing’s share of employment fell from about 21.3 percent to 8.5 percent, while professional and business services rose from 8.2 percent to 14.1 percent. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Top Picks,” https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?bls (accessed September 9, 2020).

[19]Table 1. “Union Affiliation of Employed Wage and Salary Workers by Selected Characteristics,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t01.htm (accessed January 29, 2025).

[20]Ibid. While nationwide wage comparisons of union and non-union jobs do not account for differences in things like geography, industry, and workers’ experience, economic studies that compared similar jobs have historically found a wage premium between zero and 10 percent.

[21]Ibid.

[22]Ibid.

[23]Ibid. The only industries in which the union premium did not decline between 2019 and 2023 were education and leisure and hospitality.

[24]Patrice Laroche, “Unions, Collective Bargaining, and Firm Performance,” in Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57365-6_204-1 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[25]Richard B. Freeman and Morris M. Kleiner, “Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 52, No. 4 (July 1999), pp. 510-527; Robert J. Lalonde, Gerard Marschke, and Kenneth Troske, “Using Longitudinal Data on Establishments to Analyze the Effects of Union Organizing Campaigns in the United States,” Annales d’ Economie et de Statistique, Vol. 41-42 (January- June 1996), pp. 155-185.

[26]James Sherk, “What Do Unions Do: How Labor Unions Affect Jobs and the Economy,” The Heritage Foundation, May 21, 2009, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/what-unions-do-how-labor-unions-affect-jobs-and-the-economy (accessed July 22, 2024).

[27]Domestic auto production was 6.601 million in 1994 and 1.468 million in 2024. U.S. total vehicle sales equaled 15.118 million in 1994 and 16.276 million in 2024. Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Domestic Auto Production,” updated December 6, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DAUPSA (accessed February 3, 2025), and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Total Vehicle Sales,” updated January 31, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTALSA (accessed February 3, 2025).

[28]Domestic auto production was 6.601 million in 1994 and 1.426 million in 2024. U.S. vehicle sales equaled 15.118 million in 1993 and 16.276 million in 2024. Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Domestic Auto Production,” updated February 7, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DAUPSA (accessed February 7, 2025), and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Total Vehicle Sales,” updated February 7, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ALTSALES (accessed February 7, 2025).

[29]James Sherk, “Auto Bailout or UAW Bailout? Taxpayer Losses Came from Subsidizing Union Compensation,” testimony before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, United States House of Representatives, June 10, 2013, https://www.heritage.org/testimony/auto-bailout-or-uaw-bailout-taxpayer-losses-came-subsidizing-union-compensation.

[30]Statement by Sara Schambers, member of UAW Local 182, before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, “Taking a Serious Look at the Retirement Crisis in America: What Can We Do to Expand Defined Benefit Pension Plans for Workers?,” February 28, 2024, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/f95f3998-ba66-d2ac-054a-e90e7080a705/UAW%20Hearing%20Testimony.pdf (accessed February 7, 2025).

[31]Giant Eagle, Inc. v. United Food & Commercial Workers Union, 12cv987 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 26, 2012), https://casetext.com/case/giant-eagle-2 (accessed February 7, 2025).

[32]James Sherk, “RAISE Act Lifts Pay Cap on 8 Million American Workers,” Heritage Foundation, June 4, 2009, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/raise-act-lifts-pay-cap-8-million-american-workers#_ftnref10 (accessed February 7, 2025).

[33]See, for example: The Economist, “Do Unions Increase Productivity?,” February 22, 2007, https://www.economist.com/free-exchange/2007/02/22/do-unions-increase-productivity?utm_medium=cpc.adword.pd&utm_source=google&ppccampaignID=17210591673&ppcadID=&utm_campaign=a.22brand_pmax&utm_content=conversion.direct-response.anonymous&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw-uK0BhC0ARIsANQtgGNM1crUGUpqIC1eNMavOvboc9hAIbxBbI0_- xH4HqwLgKiQdY6V8kYaAqTnEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds (accessed July 18, 2024).

[34]Hirsch, Barry T., “Sluggish Institutions in a Dynamic World: Can Unions and Industrial Competition Coexist?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Winter 2008), pp. 153-176.

[35]Mae Anderson, “Scabby the Rat Gives Bite to Union Protests, But Is He at the Tail End of His Relevancy?,” AP News, May 13, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/scabby-rat-unions-guilds-88609f4499b019ef84427851f8038420 (accessed July 18, 2024).

[36] Hirsch, Barry T., “Union Coverage and Profitability Among U.S. Firms,” The Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 73, No. 1 (February 1991), pp. 69-77. Hirsch, Barry T., “Firm Investment Behavior and Collective Bargaining Strategy,” Industrial Relations , Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 95-121.

[37] Fallick, Bruce, and Kevin Hassett, “Investment and Union Certification,” Journal of Labor Economics , Vol. 17, No. 3 (July 1999), pp. 570-582.

[38] Michael Angell, “ILA Chief Calls for Global Union Fight Against Port, Maritime Automation,” Journal of Commerce, July 25, 2023, https://www.joc.com/article/ila-chief-calls-for-global-union-fight-against-port-maritime-automation-5223460A (accessed February 7, 2025).

[39] Pacific Maritime Association, “Propelling West Coast Ports Forward,” https://www.pmanet.org/west-coast-ports/ (accessed May 21, 2024).

[40] Dr. Michael Nacht and Larry Henry, “Terminal Automation in Southern California: Implications for Growth, Jobs, and the Future Competitiveness of West Coast Ports,” Pacific Maritime Association, May 2022, https://www.pmanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Nacht-and-Henry-Automation-Report-May-2022-Final.pdf (accessed May 21, 2024).

[41] “Global Container Ports Continue To Recover From Pandemic-era Disruptions, Yet More Scope for Efficiency Gains Remain,” World Bank Group, May 18 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/05/18/global-container-ports-continue-to-recover-from-pandemic-era-disruptions-yet-more-scope-for-efficiency-gains-remain (accessed May 21, 2024).

[42]Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, data available for download at www.bls.gov (accessed February 3, 2025).

[43] See, for example: Connolly, Robert, Barry T. Hirsch, and Mark Hirschey, “Union Rent Seeking, Intangible Capital, and Market Value of the Firm,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 68, No. 4 (November 1986), pp. 567-577; and David Lee and Alexandre Mas, “Long-Run Impacts of Unions on Firms: New Evidence from Financial Markets, 1961-1999, NBER Working Paper 14709, February 2009, https://www.princeton.edu/~davidlee/wp/w14709.pdf (accessed July 18, 2024).

[44]David Lee and Alexander Mas, “Long-Run Impacts of Unions on Firms: New Evidence from Financial Markets, 1961-1999,” NBER Working Paper No. 14709, February 2009, https://www.nber.org/papers/w14709 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[45]F. Vincent Vernuccio, “Sectoral Bargaining: One-Size-Fits-All Collective Bargaining for Entire Industries,” Institute for the American Worker, March 2021, https://i4aw.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SectoralBargainingFINAL.pdf (accessed July 13, 2024).

[46] Matthias Jacobs and Matthias Munder, “A Worthy Import?: Examining the Advantages and Disadvantages of Sectoral Collective Bargaining in Germany,” International Center for Law & Economics, September 25, 2022, https://laweconcenter.org/resources/a-worthy-import-examining-the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-sectoral-collective-bargaining-in-germany/ (accessed July 13, 2024).

[47]Rachel Greszler, “In Win for Franchises, Judge Voids Biden Admin NLRB Joint Employer Rule,” May 11, 2024, https://www.dailysignal.com/2024/03/11/federal-judge-vacates-onerous-labor-rule-averting-small-business-upheaval/ (accessed June 3, 2024).

[48]Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America v. National Labor Relations Board, United States District Court, Eastern District of Texas, March 8, 2024, https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txed.226021/gov.uscourts.txed.226021.45.0_1.pdf.

[49]“Freelance Forward 2023,” commissioned by Upwork, 2023, https://www.upwork.com/research/freelance-forward-2023-research-report#:~:text=The%20Upwork%20Research%20Institute%27s%202023%20Freelance%20Forward%20survey%2C,trillion%20in%20annual%20earnings%20to%20the%20U.S.%20economy (accessed April 24, 2024).

[50]Rachel Greszler and David Burton, Comment on the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division’s Proposed Rule: Employee or Independent Contractor Classification Under the Fair Labor Standards Act [RIN 1235-AA43], December 13, 2022, http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2022/Regulatory_Comments/Comment%20Independent%20Contractor%20Greszler%20Burton.pdf.

[51]Liya Palagashvili et al., “Assessing the Impact of Worker Reclassification: Employment Outcomes Post-California AB5,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, https://www.mercatus.org/research/working-papers/assessing-impact-worker-reclassification-employment-outcomes-post (accessed April 24, 2024).

[52]James Sherk, “Auto Bailout or UAW Bailout? Taxpayer Losses Came from Subsidizing Union Compensation,” Testimony before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, United States House on June 10, 2013, https://www.heritage.org/testimony/auto-bailout-or-uaw-bailout-taxpayer-losses-came-subsidizing-union-compensation (accessed February 7, 2025).

[53] Rachel Greszler, “What Taxpayers, Workers, and Retirees Need to Know About the Union Pension Bailout That Has Nothing to Do with COVID-19,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 6059, February 26, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/IB6059.pdf (accessed February 7, 2025).

[54]U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “The Biden Administration’s “Whole of Government” Approach To Promoting Labor Unions,” 2023, https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/U.S.-Chamber-White-Paper-Whole-of-Government-Approach-to-Promoting-Labor-Unions.pdf (accessed June 3, 2024).

[55]Sean O’Brien [@TeamstersSOB], “If “Do Nothing Darren” continues he will single handily destroy a once honorable company … RESIGN NOW… Our members are done making bad investments…..,” X, June 24, 2023,5:41 pm, https://x.com/TeamsterSOB/status/1672721555426516993?lang=en (accessed June 10, 2024).

[56]Thomas Sowell, “More Social Justice ‘Fallacies’ With Thomas Sowell,” Uncommon Knowledge Interview with Peter Robinson, https://www.hoover.org/research/more-social-justice-fallacies-thomas-sowell (accessed July 22, 2024).

[57]F. Vincent Vernuccio, “Worker’s Choice: Freeing Unions and Workers from Forced Representation,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, June 1, 2016, https://www.mackinac.org/22471 (accessed September 9, 2020).

[58]F. Vincent Vernuccio and Akash Chougule, “Unions Need Democracy,” Institute for the American Worker, September 2024, https://i4aw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/I4AW-Report_Unions-Need-Democracy_Final-1.pdf (accessed February 3, 2025).

[59]The free-rider problem does not exist in forced unionism states because all workers in a unionized workplace must pay union fees as a condition of employment. In right-to-work states and in the public sector, employees cannot be forced to join or pay a union.

[60]States could allow worker-choice arrangements for public-sector employees by amending their labor laws, while Congress could allow them for private-sector workers by amending the National Labor Relations Act.

[61]F. Vincent Vernuccio, “Unionization for the 21st Century: Solutions for the Ailing Labor Market,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, November 11, 2014, https://www.mackinac.org/S2014-07 (accessed September 9, 2020).

[62]John R. Moroney and Ca Knox Lovell, “The Relative Efficiencies of Market and Planned Economies,” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 63, No. 4 (April 1997), p. 1084, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270482278_The_Relative_Efficiencies_of_Market_and_Planned_Economies (accessed April 14, 2021).

[63]Some policies to reduce government-imposed barriers to better education include: improving primary education through parental choice; reforming accreditation to expand post-secondary education options; replacing government distortions in higher education with a market-driven system; and ending the government monopoly on registered apprenticeship programs. And to improve welfare and workforce supports, policymakers should: make welfare work-oriented and independence-oriented, and replace failed federal job-training programs with more effective private, state, and local programs.

[64]Rachel Greszler, “Labor Policies for COVID-19 and Beyond: Recommendations to Get Americans Back to Work,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3506, June 30, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/BG3506.pdf.

[65]Rachel Greszler, “The Future of Work: Helping Workers and Employers Adapt to and Thrive in the Ever-Changing Labor Market,” congressional testimony before the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Subcommittee and the Workforce Protections Subcommittee of the Education and Labor Committee U.S. House of Representatives October 23, 2019, https://edlabor.house.gov/imo/media/doc/GreszlerTestimony102319.pdf (accessed September 10, 2020).

[66]PaymentAccuracy.gov, “Annual Improper Payments Datasets,” Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2024, available for download at: https://www.paymentaccuracy.gov/payment-accuracy-the-numbers/ (accessed December 20, 2024); and CBO, “Monthly Budget Review: Summary for Fiscal Year 2024,” November 8, 2024, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-11/60843-MBR.pdf (accessed February 3, 2025).

[67]Individuals’ responses to changes in pay include both substitution and income effects. The substitution effect causes people to forgo leisure for more work when pay increases (because the value of work is higher), while the income effect causes people to forgo work for more leisure when pay increases (because they can afford the same amount while also working less). In general, and absent the availability of non-earned income, the substitution effect tends to dominate, at least until individuals achieve a relatively high level of income.

[68]Paul J. Larkin, Jr., “Public Choice Theory and Occupational Licensing,” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, Vol. 39, No. 209 (2016).

[69]The Sentencing Project, “Americans with Criminal Records,” Poverty and Opportunity Profile, August 2022, https://www.sentencingproject.org/app/uploads/2022/08/Americans-with-Criminal-Records-Poverty-and-Opportunity-Profile.pdf (accessed April 26, 2023).

[70]The White House, “Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers,” July 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/licensing_report_final_nonembargo.pdf (accessed July 12, 2024).

[71]Rachel Greszler, “The Value of Flexible Work Is Higher Than You Think,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3246, September 15, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-09/BG3246.pdf.

[72]“Freelance Forward 2023,” commissioned by Upwork, 2023, https://www.upwork.com/research/freelance-forward-2023-research-report#:~:text=The%20Upwork%20Research%20Institute%27s%202023%20Freelance%20Forward%20survey%2C,trillion%20in%20annual%20earnings%20to%20the%20U.S.%20economy (accessed April 24, 2024), and Adam Ozimek, “Freelance Forward Economists Report,” commissioned by Upwork, 2021, https://www.upwork.com/research/freelance-forward-2021#:~:text=Upwork%E2%80%99s%202021%20Freelance%20Forward%20survey%20confirms%20the%20finding.,the%20eight%20years%20that%20we%20have%20been%20surveying.?msclkid=af38e75aa94311eca0aa2072597d624b (accessed May 3, 2022).

[73]Rachel Greszler and David Burton, Comment on the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division’s Proposed Rule: Employee or Independent Contractor Classification Under the Fair Labor Standards Act [RIN 1235-AA43], December 13, 2022, http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2022/Regulatory_Comments/Comment%20Independent%20Contractor%20Greszler%20Burton.pdf.

[74]Liya Palagashvili et al., “Assessing the Impact of Worker Reclassification: Employment Outcomes Post-California AB5,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, https://www.mercatus.org/research/working-papers/assessing-impact-worker-reclassification-employment-outcomes-post (accessed April 24, 2024).

[75] The 21st Century Worker Act would establish such a bright line test.

[76] https://www.global-franchise.com/insight/ifa-publishes-the-value-of-franchising-report-from-oxford-economics

[77]The NLRB issued a final rule defining joint employer status and in March 2024, a Texas federal district court vacated that rule (Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America v. National Labor Relations Board). The NLRB subsequently appealed the Texas ruling and then dropped its appeal, indicating that it will pursue similar policies through cases that come before the Board.

[78]The Save Loval Business Act would codify such a rational definition. S. 1636, 117th Congress, Save Local Business Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1636 (accessed April 6, 2023).

[79]Joseph B. Fuller and Matthew Sigelman, “Room to Grow: Identifying New Frontiers for Apprenticeships,” Harvard Business School and Burning Glass Technologies, November 2017, https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/room-to-grow.pdf (accessed April 7, 2022).

[80]“Biden to Apprentices: You’re Fired,” The Wall Street Journal, December 18, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/department-of-labor-apprenticeship-rule-biden-administration-unions-ad7c7773 (accessed March 14, 2024).

[81]The Apprenticeship Freedom Act and Training America’s Workforce Act would expand apprenticeships, including reving industry recognized apprenticeship programs. H.R. 9509, Apprenticeship Freedom Act, 117th Congress, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/9509/text/ih?overview=closed&format=txt (accessed November 29, 2023) and S. 1213, Training America’s Workforce Act, 118th Congress, https://www.congress.gov/118/bills/s1213/BILLS-118s1213is.pdf (accessed November 29, 2023).

[82]Between 2021 and 2024, inflation acted like a $16,900 tax, taking away the entirety of workers’ $11,500 nominal wage gains as well as taking away an additional $5,500 in purchasing power. Figures do not add due to rounding. Author’s calculations based on: U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Real Earnings News Release,” Table A-1: Current and real (constant 1982–1984 dollars) earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls, seasonally adjusted, March 2023, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/realer.htm (accessed April 24, 2024). Between March 2021 and March 2024, the average weekly wage increased from $1,052 to $1,193. In inflation-adjusted dollars, the real average weekly wage fell from $1,052 to $1,012 (and reached a low of $1,003 in April 2022).

[83]David Burton, “It Is Arithmetically Impossible to Fund the Progressive Agenda by Taxing the Rich,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3430, August 14, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/BG3430.pdf.

[84]Brian Reidl, “Don’t Bust the Cap: Problems with Eliminating the Social Security Tax Cap,” Manhattan Institute Issue Brief, April 2024, https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/problems-with-eliminating-the-social-security-tax-cap.pdf (accessed February 8, 2025).

[85]Adam N. Michel, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: 12 Myths Debunked,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3600, March 23, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-12-myths-debunked.

[86]Matthew D. Dickerson, “President Biden’s Corporate Tax Increase Would Reduce Wages, Harm Economic Growth, and Make America Less Competitive,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3611, April 20, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/BG3611.pdf.

[87]Rachel Greszler, “Ending the Retirement Earnings Test: A Pro-Growth Proposal to Cut Social Security Taxes and Improve Program Solvency,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3877, March 3, 2025, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/BG3877.pdf.

[88] President Donald J. Trump, “Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation,” Executive Order, January 31, 2025, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-unleashing-prosperity-through-deregulation (accessed February 4, 2025).

[89]The Working Families Flexibility Act would accomplish this goal of giving employers the right to offer, and workers the right—but not the requirement—to choose to accrue time-and-a-half paid time off instead of receiving time-and-a-half pay for overtime hours. Rachel Greszler, “Mike Lee’s Bill Would Boost Paid Family Leave Without Growing Government,” The Daily Signal, April 11, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/commentary/mike-lees-bill-would-boost-paid-family-leave-without-growing-government.

[90]Rachel Greszler, “How the Administration’s Overtime Rule Could Cost Workers More Than They Gain—Including Flexibility and Income Security,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3802, December 19, 2023, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/how-the-administrations-overtime-rule-could-cost-workers-more-they-gain.

[91]The Universal Savings Account Act (H.R. 9010) would allow individuals to save up to $10,000 per year in a Roth-style savings account for any purpose. Adam N. Michel, “Universal Savings Accounts Can Help All Americans Build Savings,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3370, December 4, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/universal-savings-accounts-can-help-all-americans-build-savings.