An initial step that has been bandied about of late has been engineering a dollar retrenchment. Even with a weaker dollar, profound challenges will be found in the rebuilding of physical infrastructure, widening vocational training, and revitalizing transportation systems. But an even more fundamental challenge lies in international disparities and expectations where compensation is concerned. Collective bargaining and higher wages have long been hallmarks of American industry, raising living standards but also making US manufacturing uncompetitive against nations with cheaper labor forces. Countries like China, India, Brazil, and Mexico can produce goods at a fraction of the US cost, owing to lower wages, and frequently with far fewer regulatory obstacles.

For decades, political candidates and labor activists alike have vacuously dangled the idea of bringing large-scale manufacturing back to the United States. Over the last ten to fifteen years, as the economic fortunes of formerly industrial regions have declined — exacerbated by globalization, automation, and a devastating opioid crisis — those promises have only grown louder.

Bringing manufacturing back to the US is a complex challenge that requires a realistic assessment of economic, logistical, and structural factors. While political rhetoric often frames reshoring as a straightforward solution to job losses and trade imbalances, the reality is more nuanced. It’s one thing to incentivize existing manufacturing firms to relocate to the US; it’s another to rebuild entire supply chains and industrial ecosystems that have lain fallow. Simply imposing tariffs or offering subsidies won’t undo decades of economic shifts overnight. Instead, a sober approach requires acknowledging the trade-offs, understanding which industries can feasibly return, and recognizing that reshoring may not necessarily lead to the same kind of job growth that manufacturing once provided.

The Labor Cost Problem

This creates a difficult, perhaps insurmountable, trade-off. If American workers demand wages consistent with the prior industrial era, domestic manufacturing will remain a stagnant relic. If wages are lowered to match global levels, domestic workers may find their parents’ or grandparents’ standards of living unattainable. Automation may provide a solution, as robots and AI-driven production could potentially make American factories far less labor-intensive and more efficient — but this would also accelerate the decline of US manufacturing jobs.

Global Supply Chains and Geopolitical Risks

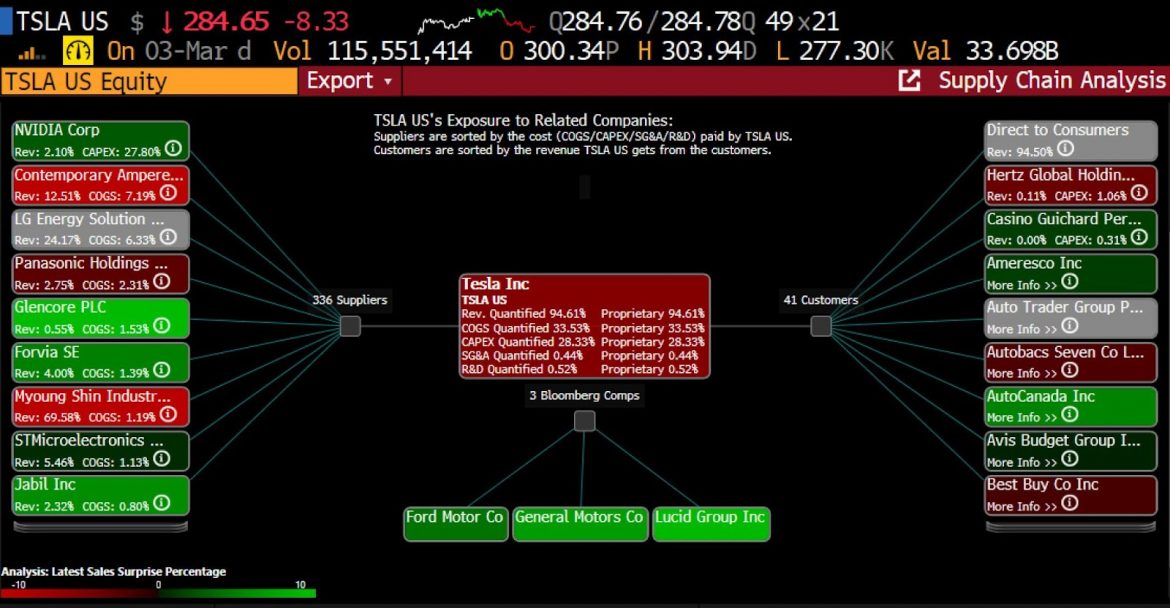

Another overlooked factor is the complexity of modern supply chains. Many products today — especially in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and automotive manufacturing — require numerous inputs across various stages of production in multiple countries. Even if new American factories sprang up nationwide, production would still depend on components from abroad. A weaker dollar — needed to make US goods more globally competitive — would make imported inputs more expensive, potentially offsetting the cost advantages of domestic production.

Global trade dynamics are constantly shifting. Geopolitical tensions with China, reshoring efforts in Europe, and supply chain disruptions (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) have revived interest in self-sufficient domestic manufacturing. However, becoming a fully self-reliant industrial power is a monumental challenge — one that would take decades, not years, to accomplish — and to doubtable benefits. Long-term plans are vulnerable to major disruptions, including technological advancements, changing manufacturing methods, and emerging financial and economic blocs, all of which could reshape the landscape significantly.

Tesla, Inc. global supply chain exposure (March 2025) (Source: Bloomberg Finance, LP)

Market approaches

If bringing back large-scale manufacturing is unlikely in the short to medium term, what might be done over a long time period? A free-market approach consistent with American foundational values would focus on minimizing government intervention while allowing the private sector to allocate resources efficiently. Summarized in one sentence, the prospects for building and running massive industrial enterprises in the United States must be made more

Here are four realistic approaches:

- Eliminate Barriers to Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Rather than artificially manipulating the economy to recreate a nostalgic industrial past, the US should focus on reducing regulatory burdens and lowering corporate tax rates to encourage investment in advanced manufacturing and high-tech industries. A dynamic, open market allows companies to allocate capital where it is most productive.

- Expand Global Free Trade and Strengthen Regional Supply Chains

Protectionism and reshoring mandates are counterproductive in an interconnected, digital economy. Instead of assuming that all manufacturing should return, the US should eliminate restrictive trade agreements that limit specialization in high-value industries. Leveraging existing advantages — such as proximity to Canada and Mexico — can improve economic outcomes without causing market distortions.

- Deregulate and Expand Workforce Development

Many American workers remain trapped in low-productivity service jobs due to an outdated education system and excessive occupational licensing requirements. By cutting red tape and investing in market-driven workforce training programs, the US can build a more competitive labor force without relying on costly, government-driven industrial policies.

4. Manage Expectations

A new generation of workers must recognize that, in many cases, the wages they have earned in recent decades have been anomalously high by historical and global standards. As economic conditions shift, the structure and role of collective bargaining in the American workplace must be reevaluated — aligning more closely with the economic realities of business rather than being treated as an entitlement. Moving forward, labor negotiations must be tied to the needs of businesses to manage costs, investments, and long-term viability, rather than ideological narratives about the alleged superiority of American labor.

In response to these challenges, there has been a growing interest in industrial policy — government efforts to actively shape and support key domestic industries through subsidies, tariffs, regulations, and strategic investments. However, these policies are closer to a pipe dream than actionable solutions. At its core, industrial policy is central planning, which inevitably leads to inefficiencies, misallocated resources, and corruption. Politically connected firms, rather than the most innovative or productive ones, tend to benefit the most.

Protectionist measures such as tariffs and subsidies often provoke retaliatory trade policies, ultimately harming exporters and consumers. Historically, industrial policy encourages complacency, leading industries to lobby for continuous government support even as they become obsolete. A more detailed economic analysis is needed to fully understand the long-term consequences of such interventions.

Pragmatism First

The era when most of the world’s industrial powers were crippled by world wars, leaving American manufacturing to thrive in a competitive vacuum, is long over. Inducing the relocation of a factory from, say, Vietnam to Ohio based on the simplistic notion that American workers are inherently “better” than their foreign counterparts is not only misguided but a hollow, pandering argument that fits better in a child’s worldview than serious economic discourse. The conditions for operating a large industrial enterprise in the United States must be at least as accommodating and advantageous as those found elsewhere — ideally, even more so.

The longer it takes labor unions, manufacturing associations, workers, and investors to adjust to this reality, the harder it will be to compete.

Political leaders benefit from oversimplifying the realities of reshoring manufacturing, ignoring the economic, logistical, and geopolitical hurdles. While industrial policy and protectionist measures promise revitalization, they are more likely to create distortions and inefficiencies than meaningful growth. Automation and technological innovation may offer a path forward, but they will not restore traditional manufacturing jobs. If the goal is to strengthen the economy, the US must prioritize reducing barriers to innovation, expanding trade partnerships, and reforming workforce development. Instead of empty promises about reviving a bygone era, the focus must be on radically reshaping how human capital is developed and deployed in a rapidly evolving global economy.