Recent polling reveals a startling development: one in four young people has a positive view of communism as an economic system.

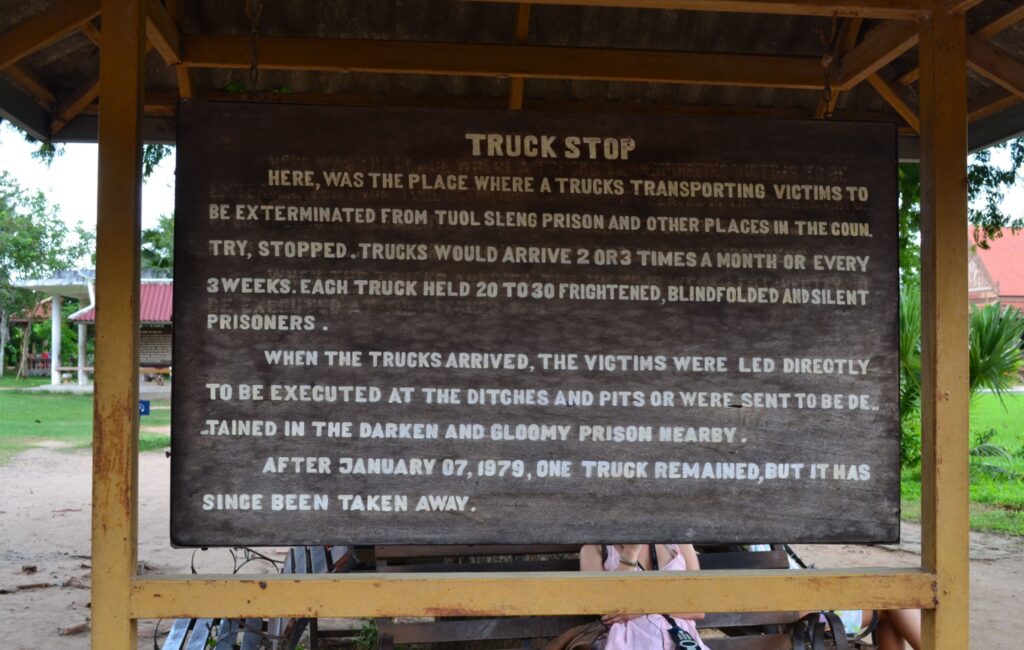

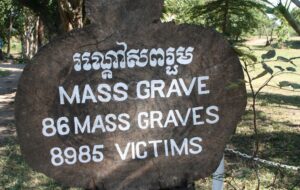

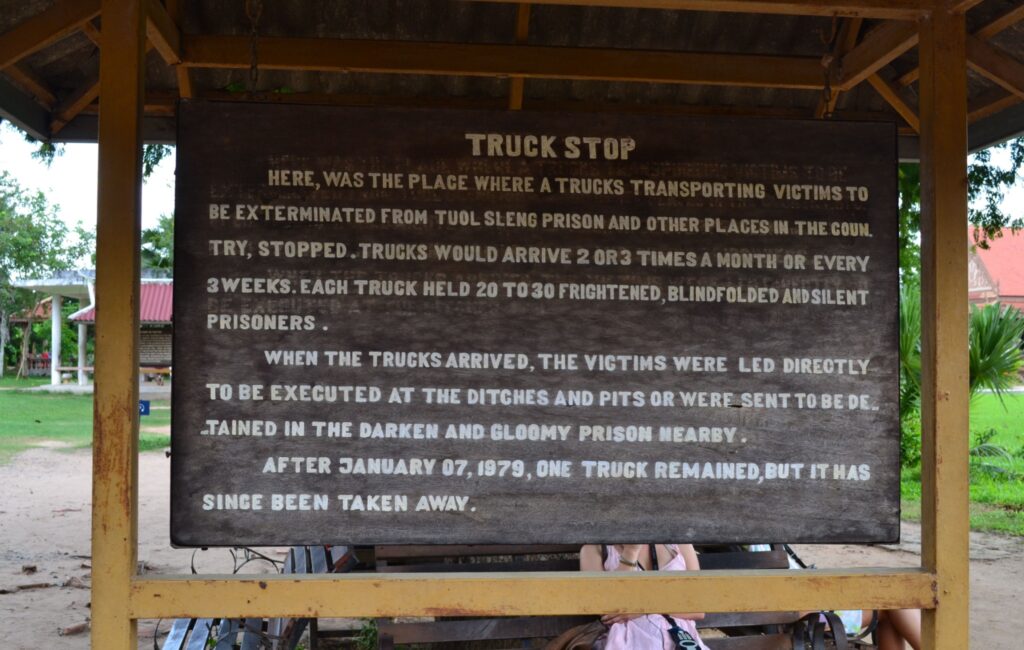

One in four is, by chance, around the same percentage of Cambodians who were murdered by the Khmer Rouge government’s policies of political torture, arbitrary execution, forced labor, mass resettlement, and brutal, intentional starvation in the 1970s. Between two and three million people were killed in just three years under a “political experiment” run by young people who were, unbelievable as it may seem, convinced they were remaking the country into a peaceful, egalitarian utopia.

When Saloth Sâr was born on May 19, exactly 100 years ago today, there was nothing in his infant heart or essential genetics that predestined him to become one of the most feared tyrants of the twentieth century. By all accounts, he seems to have been a gentle and clever child with refined manners, well-liked by schoolmates and teachers. His family farm was rural but successful, and he enjoyed a privileged education under the French colonialists who then ruled his native Cambodia. His academic pursuits eventually took him to Paris on an academic scholarship. While there, he encountered the French Communist Party and Marxist-Leninist revolutionaries.

Saloth Sâr, like many idealistic students at Harvard or Yale, saw Western capitalism as a corrosive force. He believed it was stripping Asian peasants of their nobility and moral worth. He and his friends wanted to create a new national identity and trigger a “Year Zero” event, after which all people would be equal and the needs of the poor and weak would be addressed.

This was 1959: world wars and colonialism had torn Asia apart. Saloth believed the Cambodian people deserved better than to be a puppet state of Japan or Vietnam, or a bombing buffer zone for western militaries. He had returned home to work as a teacher, and was emulating his fellow Marxist and Chinese neighbor, Mao Zedong, when he helped formalize the Communist Party of Kampuchea.

He became convinced that to return people to their natural innocence and equality, his society must be purged of the corrupting influences of banks, factories, hospitals, universities, and other modern influences. Anyone who was highly educated (besides his inner circle, of course) and anyone who chose to live in a city or practice a profession, clearly thought he was too good to be a subsistence farmer. Saloth Sar and his friends saw it as their responsibility to punish and reeducate such people to usher in an agrarian golden age of egalitarianism.

Only after returning to Cambodia would he take on the name by which he is now known, though culturally, it is a placeholding non-name, akin to Jane Doe, John Q. Public, or Joe Schmoe: Pol Pot.

The Communist Party of Kampuchea (the name for Cambodia in Pol Pot’s native Khmer language) would become known to the rest of the world as the Khmer Rouge, a horrifically murderous regime that massacred millions. But it didn’t begin that way.

The mild-mannered farmer’s son fell in love with a political vision of his country and his people, and he believed in that vision so fiercely that he would destroy both trying to perfect it.

To label Pol Pot and his close cohort as murderous psychopaths risks, as biographer Philip Short wrote, “obscuring a reality that was at once more banal and far more sinister.”

Calling what happened in Cambodia “genocide” also risks obscuring the banality of that violence and the twisted idealism of the communist cause. Pol Pot had no interest in ending the genetic legacy of the Khmer people; on the contrary, he saw himself as perfecting his beloved people, purging only those who would undermine the revolution or were insufficiently committed to the future, perfect society. As the communist regime failed (as all communist regimes do), the search for scapegoats and traitors turned more and more people into acceptable sacrifices for the greater good.

And Pol Pot could not have done such horrors alone. Thousands of people helped him. Once the vision of a perfect, Communist Kampuchea took hold, many people — even as they who saw their own families murdered, their children kidnapped, their homes burned, their friends exiled, their cities emptied — would continue to believe in the dewy, sepia-tone vision that had begun germinating in intellectual salons in Paris. The intellectuals who survived defended their participation in the communist “political experiment” that made them literal slaves to the state.

Even as the Khmer Rouge abolished the notion of the family and made children into Party property, some believed. When peasants were stripped of clothing and forced into shapeless uniforms, and city dwellers were pushed onto collective farms and then onto killing fields, many believed it was for the best, a necessary sacrifice for a glorious future. Like the young Saloth Sâr, they subscribed to an unconstrained vision in which society and human nature itself could be remade by the sheer force of political will. Individual lives were nothing to a totalitarian strong man who possessed the nerve to do what must be done.

“To keep you is no benefit,” went the Khmer Rogue slogan, “to destroy you is no loss.”

The very ideas of freedom, individuality, creativity, intellectual self-betterment — they had become anathema to being a good Cambodian. Freiderich Hayek wrote in The Road to Serfdom, “If the feeling of oppression in totalitarian countries is in general much less acute than most people in liberal countries imagine, this is because the totalitarian governments succeed to a high degree in making people think as they want them to.” Pol Pot had made his communist fever dream into every Cambodian’s living nightmare.

Money was abolished. Mass communications — radio, newspapers, even public gatherings — were eliminated. Private travel was banned, cutting people off from one another completely.

Religious practices, including Buddhism, were also banned. The Khmer Rouge controlled all sources of information, and few could resist the ideological narrative of government power being used to reorder humanity for its own benefit. Those who tried to resist were imprisoned, tortured, disappeared, or executed.

“To keep you is no benefit,”

went the Khmer Rogue slogan,

“to destroy you is no loss.”

In the intellectual echo-chamber of Marxist universities, a toxic narrative of “us” vs “them,” and a hideous pretense of knowledge reigned, then, as now. Young Saloth Sar, with his refined manners and his imperfect French and his engineering scholarship, almost certainly didn’t envision becoming one of history’s greatest murderers. He was the victim of an unconstrained vision, and corrupted by undisputed power. He fooled himself with a beautiful lie, and in his conviction to enact it, came to see human beings as disposable.

“Our policy was to provide an affluent life for the people,” Pol Pot explained in an interview with journalists after he was deposed. “There were mistakes made in carrying it out.”

Hundreds of millions more faced starvation in the years that followed Pol Pot’s fall, most of them already-starving peasants reliant on an agricultural daydream, ravaged by war and incompetence.

One architect of the Khmer killing fields, Khieu Samphan said, returning to the capital 20 years after the slaughter: “I would like to say sorry to the people. Please forget the past and please be sorry for me.” Such was the recompense for a terroristic regime, what The Guardian called, “a four year reign of homicidal terror that, even in a century featuring such butchers as Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, was almost too shocking to believe.”

But the world didn’t just look away. Many around the world, experimenting with mid-century Marxism, wanted to believe in Pol Pot’s vision for Cambodia, too. Western powers, already exhausted by proxy wars in South East Asia, watched with indifference. And western journalists, many of whom were Marxists themselves, reported glowingly of Pol Pot’s “experiments.”

“It remains a mystery to me that we could have been so fooled,” wrote Gunnar Bergström, a Swedish journalist who took a propaganda tour in 1978. He said, in a later apology, “we were fooled by the smiles, but maybe most of all by our own Mao-glasses.”

In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek reassured readers that the intellectuals and central planners of our acquaintance “would recoil if they became convinced that the realization of their program would mean the destruction of freedom.” But Saloth Sar is one poignant reminder that few leaders can be stopped, or will stop themselves, from imposing their tyrannical will “for our own good.” And that too many of us will be willing to look away.

Radicals and revolutionaries might capture the hearts of young people, but they cannot be allowed to capture centralized power. Only a respect for the individual and a respect for civil liberties can shield us from the “good intentions” of idealistic social planners with all their devastating, murderous, totalitarian consequences.