Over the years, I — like all defenders of free trade — have had countless conversations with protectionists who are tenacious in searching for weaknesses in the case for free trade. What follows is a composite of some key exchanges in many of those conversations. Every point below that “Protectionist” makes is one that real people have served up to me on several occasions. Except for the composite nature of this conversation between “Protectionist” and “Boudreaux,” nothing is fictional.

Protectionist: Over the past half-century, American industry has been hollowed out by international trade. We don’t make things anymore. That’s why we need protective tariffs.

Boudreaux: You’re factually incorrect. US industrial output hit its all-time peak in February of this year, higher by 155 percent than it was in 1975, when America last ran an annual trade surplus and 19 percent higher than in 2001, when China joined the WTO. Also, US industrial capacity is at an all-time high, and 147 larger than in 1975 and 12 percent larger than in 2001. Tariffs only —

Protectionist: Sorry for interrupting, but I don’t believe those government statistics. Bureaucrats are politically biased, with no incentive to get things right.

Boudreaux: Do you hear yourself? You don’t trust government officials to competently gather and report economic statistics, yet you do trust government officials with the power to coercively obstruct your and other Americans’ peaceful commerce with foreigners. How does that make sense?

Protectionist: I know what I see. Boarded-up factories, ruined lives, nothing made in America. You’re telling me that my own eyes are lyin’. I’m telling you that I believe my eyes and not free-traders’ lies, damn lies, and statistics.

Boudreaux: How many boarded-up factories do you actually see — in reality, not in photos — on a regular basis? If what we literally see with our eyes is the only guide to reality, then my eyes, seeing not a single shuttered factory, tells me that no such things exist. Whose eyes should be believed? Even if you happen regularly to encounter such sights, these aren’t the norm in the US We need statistics to get an accurate picture of the economy.

Now it’s true that statistics can mislead, but they can also reveal and enlighten. It’s foolish to leap from the fact that statistics are sometimes used deceptively or carelessly to the conclusion that all statistics are unreliable. Indeed, you yourself rely on statistics whenever you assert, as you often do, that nineteenth-century US economic growth was fueled by tariffs. After all, your eyes weren’t around in the 1800s to do any observing. Your argument depends on you knowing that, in that era, US tariffs were often high and America’s economy grew at a rapid pace — both bits of knowledge being statistical.

Protectionist: Look, all I know is that America had high tariffs in the high-growth nineteenth century. Hard to argue with that!

Boudreaux: Actually, even beyond pointing out that you commit the sophomoric error of mistaking correlation for causation, it’s quite easy to argue with your assertion. Phil Gramm and I, in our new book The Triumph of Economic Freedom, look at annual growth rates of US industrial production in the nineteenth century. We find that industrial output grew faster in periods when tariff rates were falling than in periods when tariff rates were rising.

But beyond this fact, America back then was economically quite free, very entrepreneurial, and so large that most economic activity was purely domestic. International trade played a relatively minor role in nineteenth-century US economic growth. A greater role was played by immigration. According to the economic historian Robert Higgs, the US in the latter half of the nineteenth century experienced “the greatest volume of immigration in recorded history.”

If you conclude that the co-existence in nineteenth-century America of protective tariffs and rapid economic growth proves that protective tariffs fuel economic growth, then you logically must also conclude that the co-existence in nineteenth-century America of enormous immigration and rapid economic growth proves that enormous immigration fuels economic growth. Should we return today to the immigration policy that reigned in the US in, say 1870, when our borders were almost completely open?

Protectionist: Let’s stick to tariffs, shall we? When I go to Walmart and Target, or buy stuff on Amazon, all the labels read “Made in Vietnam,” “Made in Bulgaria,” “Made in Mexico” — never “Made in America.” Nothing today is made in America. My eyes don’t deceive me.

Boudreaux: No, but your limited knowledge does. Those labels don’t mean what you think. In today’s global economy, the great majority of the manufactured goods that you consume consist of parts and ideas from around the world, including the US. A “Made in” label on some good tells you only where that good’s final assembly occurred. Bath towels at Target labeled “Made in Turkey” might well be made of cotton grown in Texas, dyed with pigments from Germany, woven on a loom made in India, and shipped to the US on a freighter made in Korea that is carrying a shipping container manufactured in Denmark. That label would be more accurate if it instead read “Final Processing Done in Turkey” — or, more accurate still, “Made on Earth.”

Because the final processing of most consumer goods is a relatively low-value-added task, Americans’ high wages make it worthwhile for manufacturers to have those tasks performed by lower-wage non-Americans. But goods labeled “Made in Turkey” or “Made in China” frequently contain more inputs made in the USA than in the country named on the label.

Protectionist: Well, maybe some parts of the US are doing okay economically, but you can’t deny that the rust belt has been devastated by the decline of manufacturing there.

Boudreaux: I do deny it. Manufacturing output in the Rust Belt hasn’t declined, at least not in the past twenty years. The St. Louis Fed has quarterly data on real manufacturing output by state going back to the first quarter of 2005. Even in the Rust Belt, manufacturing output over the two decades from then through today (the fourth quarter of 2024) has risen. The inflation-adjusted aggregate manufacturing output of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Wisconsin is today 14 percent higher than it was twenty years ago.

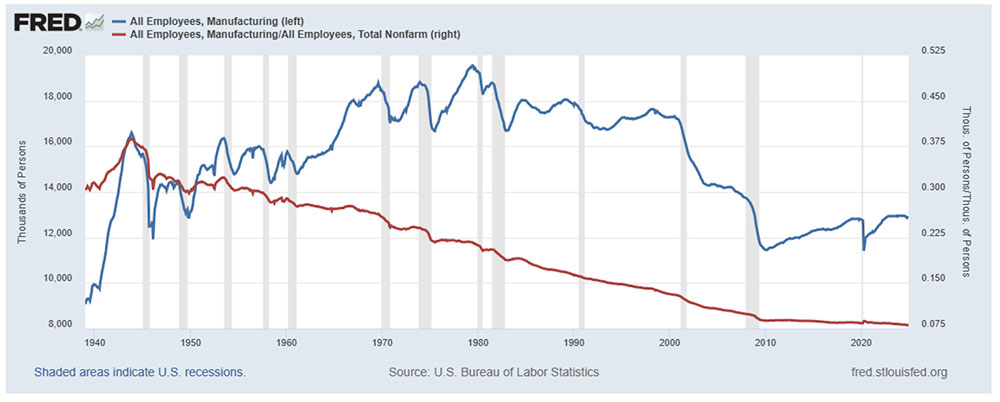

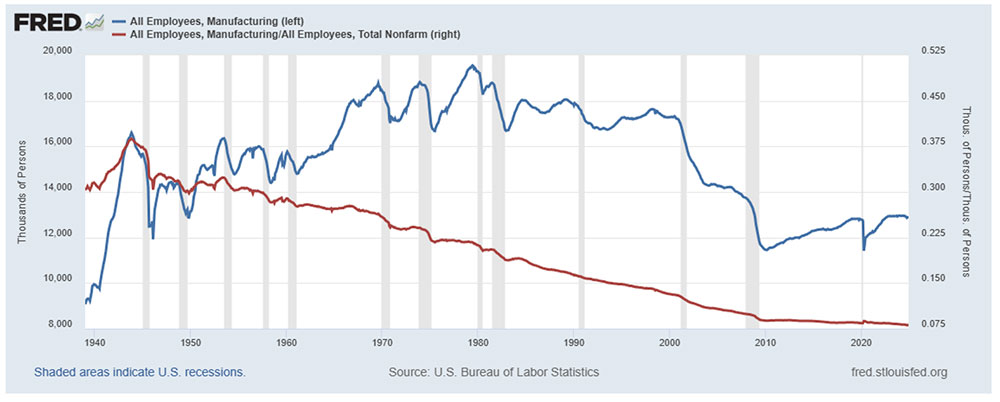

What has declined over the past twenty years is the share of the total workforce employed in manufacturing jobs. But this trend didn’t start twenty years ago, or thirty years ago, or even fifty years ago. It started seventy years ago, in 1954. Indeed, this decline has slowed somewhat since China joined the WTO in December 2001. From January 1954 through November 2001, manufacturing employment as a share of total nonfarm employment fell at an average monthly rate of 0.165 percent. From December 2001 through today (April 2025), that rate of monthly decline slowed to 0.146 percent.

If you’re looking for a culprit to blame for the loss of blue-collar jobs, don’t look at trade and offshoring — again, US industrial output is now at an all-time high — look instead at labor-saving technology. Look instead at the very same economic force that a century earlier caused the loss of agricultural jobs. Human ingenuity, much of it American, that improves technology is to blame, not trade.

Protectionist: Whatever. If higher tariffs here can restore manufacturing employment, ordinary Americans will be made better off.

Boudreaux: Do you have children?

Protectionist: Huh? Don’t change the subject.

Boudreaux: I’m not changing the subject. Do you have children?

Protectionist: Three. Two in college, one in high school.

Boudreaux: I applaud you. What do they study?

Protectionist: I still don’t see what this has to do with trade…. The oldest is graduating with a degree in finance, and my daughter is studying nursing. My youngest wants to be a musician.

Boudreaux: You have every reason to be proud! But not one of your kids seems to want to work in a factory.

Protectionist: Straw-man argument. I didn’t say that every American wants to work in manufacturing, just that more do.

Boudreaux: How do you know that? What do you do for a living?

Protectionist: I’m an accounts manager for a furniture wholesaler — I know, it’s not a manufacturing job. But look, I also know that we have a shortage of manufacturing jobs because, well, we hear all the time that Americans want more manufacturing jobs.

Boudreaux: Not everything you hear is true. Unemployment today is low and real wages are at an all-time high — two facts that, together, are practically impossible to square with the frequently repeated assertion that ordinary Americans are suffering because of a lack of manufacturing-employment opportunities. The reality is that manufacturers are having a difficult time finding and retaining workers. The average number of monthly manufacturing job openings since this century began is 365,000, but today (March 2025) that number stands at 449,000.

Nearly all parents want their kids to grow up to be the likes of doctors, lawyers, and architects, not welders, pipefitters, and assemblers on a factory floor. And that’s also what their — and your — kids want.

Protectionist: Your elite disdain for regular people is repellent.

Boudreaux: You mistake me. I have no such disdain. I admire manufacturing workers, as I admire anyone working in an honest job. My late father, whom I admired beyond words, spent his career laboring in a shipyard. But I don’t want such a job, and my dad would have thought me crazy if I’d quit college to work alongside him. Those lost manufacturing jobs for which you have nostalgia were generally difficult, dangerous, and unpleasant — I know, because I worked in that same shipyard during the summers when I was in college. It’s a blessing that there are fewer and fewer such jobs.

Protectionist: Yeah, but you overlook—

Boudreaux: Now I must apologize for interrupting you. It’s getting late. Perhaps we can resume this conversation sometime in future.