To those who know some economics, the phrase “Foundations of Economics” leads them to expect to hear about things like the rule of law, property rights, contracts, supply and demand, and so forth. These are indeed among the most foundational ideas in economics. Rest assured that this explainer series will cover them and more, with enthusiasm.

But cooperation is where the real story of economics actually begins.

It is by understanding the nature of cooperation that one can see how the evolution of all the other foundations of economics, and even the free market economy itself, was driven by the societal benefits from ever more effective cooperation. Yet cooperation’s basic logical structure and its central and continuing role in driving the development of free market institutions are largely underappreciated. Our free market economy is the most effective engine of cooperation ever achieved by humans. Every economist – indeed every citizen – should be able to clearly explain why. We’ll begin by exploring why human cooperation is so much more effective than in all other species.

What Makes Human Cooperation Different?

Cooperation is common in nature. Social insects such as ants and bees dominate our planet in number and biomass. They cooperate through almost perfectly coordinated behavior derived from genetically encoded “if-then” protocols. But while such cooperation is powerful, it is also very inflexible.

Suppose a fungus wiped out all the clover in a given area and a flower, whose nectar was perfectly good food for bees, replaced the clover. If the new flower’s scent is not recognized by the bees as an “if” predicate, so it can be followed by a “then” response to collect its nectar, most of the hives in the area will die.

Other species like wolves and orcas are able to cooperate in flexible ways that allow for behavioral adaptation to changing circumstances within the same generation. They are not effectively cooperating solely through genetically programmed coordination. They are consciously cooperating by thinking about what they do. But with the exception of humans, this kind of consciously rational cooperation only works for very small groups.

Humans also teach new behavioral responses to their neighbors and their children. New forms of behavior therefore don’t have to be relearned each generation. When Spaniards’ horses arrived on the American continent, Comanche parents didn’t just adapt behaviorally, devising new strategies for hunting and waging war. They also changed what they taught their children, developing an all-new culture of horsemanship and husbandry.

Unfortunately, the larger the group, the more likely individuals will be tempted to promote their welfare at the expense of the group. This is because in a large group, one individual’s opportunism (say, cheating on his taxes) can be so small relative to the group that the group is not noticeably harmed.

Obviously, if undetected, the individual gets 100 percent of the benefit from promoting his welfare at the expense of the group. But the larger the group, the more likely it is that the cost to any one individual is too small to notice.

The problem is that if all individuals think and act this way, it leads to disaster. If one individual cheats on his taxes, he benefits greatly, and society marches on because the effect on tax revenues is less than a rounding error. But when everyone cheats, the government will collapse.

This free-rider problem explains the tradeoff between flexibility and scale of cooperation: the more behaviorally flexible individuals are, the more opportunities to engage in opportunism. Such opportunism can end up destroying some or all of the gains from cooperation. This is a pervasive problem for species that live in large groups, as Garrett Hardin demonstrated in his memorable 1968 masterpiece The Tragedy of the Commons.

This tradeoff nearly always keeps species that have the ability to cooperate flexibly from being able to cooperate flexibly in large groups at the same time.

Consider this table:

| LARGE GROUP | SMALL GROUP | |

| FLEXIBLE | ? | Wolves |

| INFLEXIBLE | Caribou | Wasps |

Are there any species that can be put in the LARGE GROUP/FLEXIBLE category? The answer is yes, but only one – Sapiens.

Flexible large-group cooperation has existed for our species, Sapiens, for a long time. But while Sapiens cooperated in groups that were large compared to other flexibly cooperating species, they were not large compared to the groups humans frequently cooperate in today.

After Malcolm Gladwell discussed his work in the bestselling book The Tipping Point, anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar became an international scientific celebrity for his finding that human groups function best at around 150 people.

Luckily for us, culture, in the form of knowledge passed from generation to generation by teaching and learning, provided a way of overcoming this tradeoff. Because humans are uniquely gifted at teaching and learning, we were able to use our extraordinary capacity for culture to stretch flexible cooperation far beyond Dunbar’s number.

For many important behaviors, where consistency is paramount, culture also gave us a means of encoding behavior that provided regularity, as we see with social insects. But since behavioral responses aren’t hardwired, it still allows for flexibility, like being able to teach your children differently than how you were taught.

Our pre-Sapiens ancestors competed intensely with each other. They became locked in a kind of arms race of improved ability to culturally encode behavior to improve cooperation. Traits that supported the ability to do this were reinforced in the gene pool until modern humans prevailed.

The link between the evolution of the traits that support culture and those that support cooperation is so strong that there is now a consensus among anthropologists and evolutionary psychologists that the genes that make us unique arose from the evolutionary payoff of using culture rather than genes to facilitate cooperation.

A Tale From a Fishing Village

Picture a fishing village on the banks of a small river about 25,000 years ago. One morning, two cousins were spearfishing about 100 yards apart on the river. They stood perfectly still, waiting for a fish to swim by. If a fish was big enough and close enough, they threw their spear. In this way, they normally speared about three fish per hour.

The younger of the two cousins threw at a fish that was too far away, so his spear skipped across the water and was now floating downstream. He waded out to get it, but he could barely keep up with the current. Meanwhile, his cousin was now spearing fish after fish.

Later, they conjectured that while wading after his spear, the younger cousin was herding fish toward the older one, dramatically improving his odds.

The next day, they took turns herding and spearing and got 12 fish per hour! This is twice as many fish per person per hour! Doubling the productivity of fish spearing in a village whose way of life depends on eating fish is an incredible thing. They became the talk of the tribe. Almost immediately, others began copying them. By fishing in this cooperative fashion, many more fish were harvested for the group.

This is a wonderful outcome, but it also presents new challenges. (In a future explainer, we’ll employ the argument Garrett Hardin made in The Tragedy of the Commons to explore how humans were able to use culture, institutions, and government to protect the growing benefits of cooperation from the growing temptation to be opportunistic.)

How Cooperation Works

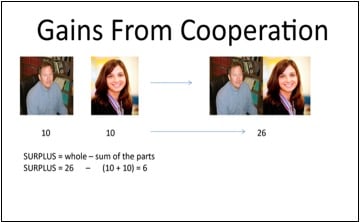

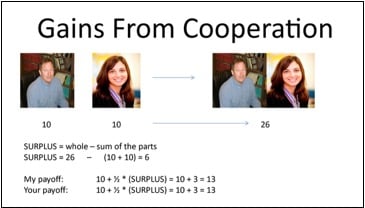

Suppose that, working alone, I make 10 units of something, and you can, too. But by cooperating we can make 26 units. Not 20, which is what your mind was expecting, but 26. This is because when we cooperate, we are more effective than when we work alone.

Think about making birdhouses. Having two people work together makes it possible to divide the tasks. Adam Smith called this specialization through the division of labor. As he explained in 1776 in his masterpiece The Wealth of Nations, dividing up tasks can dramatically increase output per person. As a child, you may have built a fort in the woods with your friends. The first thing you and your friends did was to divide up the tasks because it was so obvious that doing so would be more effective.

Smith then argued that the larger the group, the more finely labor can be divided. He argued that this should increase output per person even more. Smith was indeed the first to precisely understand why large group cooperation is so much more effective.

Returning to our first example, the main point is that the value of the whole, 26, is clearly greater than the value of the sum of the parts (10 + 10). This difference of 6 is so important that we give it a name. We call it the cooperative surplus.

The cooperative surplus is the key to it all. It’s how humans create exponentially more value together than they could alone—so that everyone benefits at the same time. And since having more per person is the first step to increasing general prosperity, it follows that cooperation is what ultimately makes societies prosper.

Even a toddler understands that he can make himself better off by taking what someone else has, but that obviously makes the other person worse off. This sows the seeds of hate, conflict, and revenge. But when we cooperate, we do better than toddlers. With cooperation, there’s a cooperative surplus that can be divided among cooperators, making it possible for everyone to benefit—so no one has to lose. This sows the seeds of friendship, harmony, and peace.

The cooperative surplus is the key to all cooperation. Countless books and studies explore cooperation, but none of it matters without a cooperative surplus. Because without one, there’s no real advantage to cooperating at all.

Dividing Output

Some ideas are simple yet powerful. Cooperation is one of them. Another is the idea of opportunity cost from economic theory.

The opportunity cost of doing something is everything that must be given up to do it. So the opportunity cost of going on a date is not just the cost of dinner and a movie. It also includes the cost of gas and even the money you won’t earn because someone else covers your shift at work.

People who are good at thinking in terms of opportunity cost do a better job of imagining all the possible costs of taking actions. This leads to better decision-making.

So what does opportunity cost have to do with cooperation?

It’s the first step to understanding how to divide the fruits of cooperation. That might seem obvious at first—especially in simple examples where the answer feels intuitive. But be patient.

Soon we’ll be able to use this procedure to understand how to divide output in more complicated settings in which the best way to divide output is often far from obvious.

Before we begin, let’s be clear: we’re not talking about coerced cooperation. We’re assuming that everyone involved is genuinely free to decide whether or not to cooperate.

So, how should the final 26 units from our example be divided? Your gut might say “split them evenly”—and in this case, you’d be right. But chances are, you’d be right for the wrong reason. And not understanding why an equal split is correct can lead to mistakes with devastating consequences for free societies.

So what’s the right way to think about it? First, both you and I must receive at least 10 units each. Why?

Because we can each produce 10 units on our own if we choose not to cooperate. That makes 10 the opportunity cost of cooperation for both of us. And since we’re free to walk away, it follows that neither of us would agree to cooperate for less than our opportunity cost.

So of the 26 units to be divided, 20 are already spoken for in a free society. That leaves 6 units—the cooperative surplus.

These 6 units wouldn’t exist without cooperation, so they belong to neither of us individually. They are, in fact, ours. And because neither of us has a stronger claim to them, the only fair way to divide them is equally.

If, for example, I got 4 and you got 2, you could reasonably ask: “Why do you get more than me, when your claim is no stronger than mine?” By sheer logic, we arrive at the conclusion: each of us should get 3 of the surplus.

So I get 10 for my opportunity cost and 3 as my share of the surplus—13 in total. The same goes for you. Since 13 + 13 = 26, this division is both fair and efficient. It accounts for every unit of output and doesn’t waste anything.

Your first reaction might be: “That’s just splitting 26 in half—so why go through all these steps?” And you’re right that in this simple example, the result is the same as an even split.

But in the next explainer, we’ll see that when the example becomes just a bit more complex, this method no longer yields an even split. That happens when two principles we deeply value remain true:

- Everyone is free to cooperate however they choose, as long as they don’t coerce anyone.

- Everyone is treated equally.

References

Boyd, Robert, and Richerson, Peter J. 1985. Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dunbar, Robin I.M. (2016). Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2000. The Tipping Point. Little, Brown and Company.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2015. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162(3859), December 1968, 1243-1248.

Henrich, Joseph. 2007. Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation. Oxford University Press.

Henrich, Joseph. 2017. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Price, Michael. 2017. “True Altruism seen in chimpanzees, giving clues to evolution of human cooperation.” Science, June 19, 2017.

Ridley, Matt. 1998. The Origins of Virtue: Human instincts and the evolution of cooperation. Penguin Books.

Rose, David C. 2019. Why Culture Matters Most. Oxford University Press.

Rose, David C. 2000. “Teams, Firms, and the Evolution of Profit Seeking Behavior.” Journal of Bioeconomics, Volume 2, Number 1, 25-39.

Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Book 1, Chapter 1: https://www.rrojasdatabank.info/Wealth-Nations.pdf