Even though the COVID-era inflation surge is in the past, Americans are right to remain concerned about the state of our money. Contention over America’s monetary policy is nothing new, however, and sound money advocates can find inspiration in revisiting the prominent money debate, which enraptured much of American politics at the end of the nineteenth century. This period, known as the Gilded Age, was in many ways a captivating and busy time. In the years following the American Civil War, there was remarkable economic growth and productivity, but also a litany of issues facing the country, not the least of which revolved around monetary policy.

By the final decade of the nineteenth century, amid the Panic of 1893 and political factionalism, the debate over America’s money reached a climactic showdown. As this uneasy situation was unfolding, agrarians and Western miners wanted an inflationary “free silver” policy to relieve their debts and benefit their economic interests. In contrast, many classical liberals and conservatives favored a firm adherence to the gold standard on the grounds of prudence, stability, and connection with international trade. These diverging perspectives were personified in the rhetorical battle between William Jennings Bryan and Carl Schurz during the 1896 presidential campaign. The resulting war of words offers meaningful insights for those who support sound money and markets in our own time.

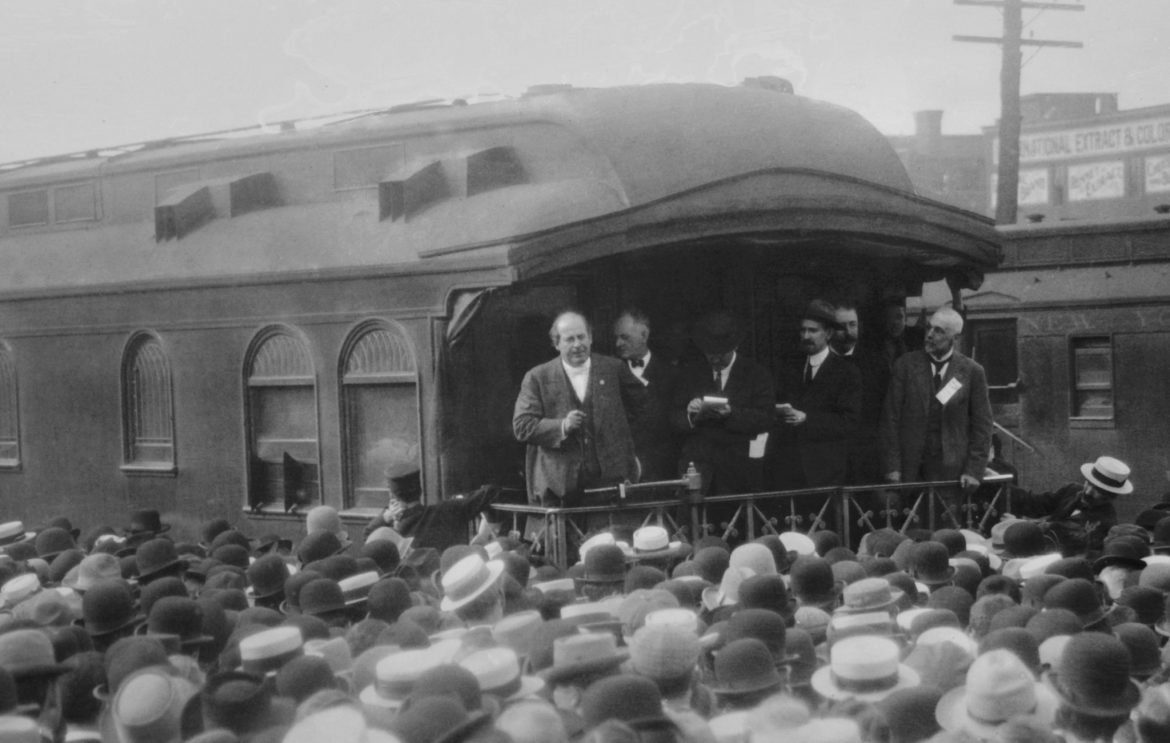

In 1896, the chief spokesman for inflation was the young Nebraskan William Jennings Bryan. At just 36 years old, Bryan was the presidential candidate for both the Democratic and People’s (Populist) parties. While he did not invent the concept of free silver, he was by this time its most potent advocate after delivering his captivating “Cross of Gold” speech at that summer’s Democratic National Convention. This famous speech reflected the inflationist position as Bryan referred to the gold standard as a “crown of thorns” upon the “brow of labor,” and concluded with the declaration, “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Once nominated, Bryan toured the country in support of his inflationist and interventionist platform, which proclaimed that “the money question is paramount to all others at this time.” Bryan utilized a variety of tactics in his campaign, such as invoking class and regional rivalries, as well as frequent references to his Christian faith. Despite his oratorical energy and outward allegiance to the “plain people” of the country, not all Americans were sold on Bryan and free silver, however, as classical liberals were quick to demonstrate.

One outspoken Bryan critic was Carl Schurz, a German immigrant, Civil War veteran, Senator, political commentator, and determined classical liberal. Schurz was involved with several classical liberal causes in the Gilded Age, one of which was his firm advocacy of sound money. In direct response to Bryan, Schurz delivered a speech of his own in September 1896 in Chicago, the same city where Bryan had made history with the “Cross of Gold” in July. Schurz’s response was entitled “Honest Money and Honesty,” and it was a detailed rebuttal to multiple arguments Bryan employed in his campaign. Schurz’s speech served as a powerful case for sound money, the importance of which carried beyond the nineteenth century and into ours.

One of the concerns Schurz sought to address was the perceived instability that many sound money advocates thought a Bryan victory would have meant for the economy. Americans were already dealing with the continuing economic debacle stemming from the Panic of 1893, and it was unclear whether free silver would cause a resolution of these issues or more of the same, if not worse. Although Bryan pitched his free silver campaign as a method to relieve the suffering of many Americans, others saw it as a sign of impending inflation, instability, and national dishonor. There is even evidence to suggest that Bryan’s pro-inflation campaigning itself further fueled economic uncertainty as the future of the American economy seemed unclear. In this atmosphere Schurz took aim at the economic risk posed by Bryan and his calls for free silver inflation.

The issue, as Schurz saw it, was that Bryan’s calls for inflationary policy were addressed primarily to lower-income Americans such as farmers, miners, and urban laborers. Schurz called these “deceptive appeals” to wage-earners “the most heartless and damnable” of Bryan’s tactics because he recognized that these were also the people who stood to be most negatively impacted by an increase in the money supply and the attendant rise in prices. Schurz aptly recounted the momentous increase in prosperity which characterized the nineteenth century, a situation which has been borne out by economic studies of the period, despite the efforts of some academics to maintain the image of the Gilded Age as one simply of inequality and cartoonish Robber Barons. Rather, Schurz understood that only through the preservation of sound money, and not the freewheeling inflation of free silver, could the American economy continue the growth which had improved people’s lives throughout the nineteenth century.

Additionally, Carl Schurz countered Bryan’s argument on moral grounds, further demonstrating that the “money question” was as much an ethical disagreement as an economic one. He offered a religious metaphor of his own in a direct response to Bryan’s frequent invocation of Christian imagery on the campaign trail. Schurz likened Bryan and free silver to a “temptation” presented to the American people and noted: “Mr. Bryan has a taste for Scriptural illustration. He will remember how Christ was taken up on a high mountain, and promised all the glories of the world if he would fall down and worship the devil. He will also remember what Christ answered. So the tempter now takes the American people up the mountain and says, ‘I will take from you half of your debts if you will worship me.’” Yet, despite Schurz’s allusion to Bryan as a dangerous “tempter” akin to the devil, he was confident that the American people would see through his scheme and that “the Stars and Stripes will continue to wave undefiled, honorable, and honored among the banners of mankind.”

While William Jennings Bryan ultimately lost the 1896 election and the pro-gold McKinley became the president, the arguments employed in the debate over monetary policy reach beyond the confines of the late-nineteenth century and into our present day. It is true that the question no longer revolves around disputes over silver and gold, but the principles of sound money advanced by classical liberals like Carl Schurz are worthy of consideration because of their timeless insight into the nature of inflation and the moral and economic hazards it invites. As Americans in our own era have experienced the harmful effects of inflation in the wake of COVID, perhaps we can stand to benefit from learning from previous generations of sound money advocates.