In the mid-to-late 19th century, crimes such as murder, robbery, and cattle rustling plagued America’s western frontier. Although the West was not quite as “wild” as Hollywood portrays, it was far from tame.

Between 1866 and 1910, there were nearly one thousand train robberies in the US, according to historian Michael Wilson, the vast majority of which occurred in the West.

Yet, on a frontier where government law enforcement was spread thin, private individuals came to the rescue through bounty hunting and private detective agencies.

Throughout the Old West, private firms, individuals, and government authorities offered rewards for the capture and conviction of fugitives, typically advertised by newspaper ads or circulars.

The Tombstone Epitaph, for instance, reported 31 separate reward offers involving Cochise County, Arizona, between August 1887 and 1893—a county that reported fewer than 7,000 residents in the 1890 census. Roughly half of these were offered by private parties. One such ad from the March 15, 1891, edition of the Tombstone Epitaph reported the following:

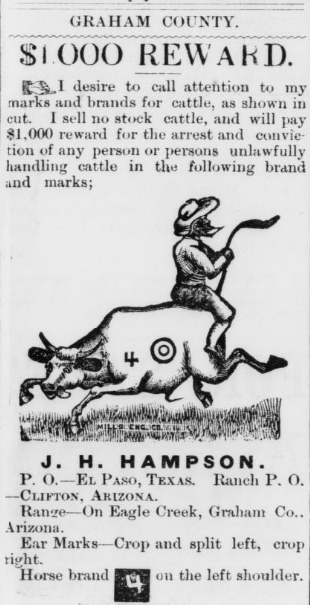

Another ad in a June 17, 1886 edition of Hoof and Horn, a Prescott, Arizona newspaper largely devoted to livestock news, posted a standing bounty for cattle rustlers:

In this way, bounties gave victims a way to seek justice for fugitive crimes without simply waiting around for government lawmen to do their job. Instead, individuals took action to root out lawlessness, including property theft.

Similarly, large firms that frequently dealt with criminals, such as railroads and express companies, often hired private detectives to fight and deter crime.

Wells Fargo, notably, had an in-house detective agency to investigate stagecoach stickups, train robberies, and burglaries. Between 1870 and 1884, the firm reported 340 stagecoach robberies, train robberies, and burglaries with losses totaling over $400,000 and paid out over $70,000 in rewards, according to internal records compiled by company detectives James B. Hume and John N. Thacker. During the same period, Wells Fargo secured 240 convictions—a great record given the erratic nature of courts in the West and the extreme difficulty of apprehending fugitives on the sparse, expansive frontier.

While lawmen did hunt fugitives, they often did so only when rewards were offered. According to historian Larry Ball, lawmen were typically part-time and spent most of that time collecting taxes, cleaning streets, or dealing with local crime. Western lawmen were paid little, usually through a combination of small fees for arrests (typically $2 each), small salaries, or a commission out of tax collections. Moreover, they typically presided over massive jurisdictions. Because of this, few lawmen were willing to embark on dangerous and costly fugitive hunts without additional compensation.

With public law enforcement’s lackluster performance, private parties had to offer bounties if they wanted justice—and they did just that. While vigilance committees offered another alternative for law enforcement—and were rather common, with at least 210 vigilante movements in the West between 1849 and 1902, according to historian Richard White—these weren’t suited for every circumstance. Many communities formed vigilance committees to root out crime when the government failed to act, but these organizations also required collective action. Such endeavors, while suitable for local crimes affecting many, would be incredibly costly when justice demanded an expensive search for fugitives that might only impact a handful of community members. This was where bounty hunting and private detectives stepped in.

For public officials, meanwhile, bounties signaled to their constituents that they cared about law and order, therefore helping their chances of re-election or other career advancement. Additionally, such measures were far cheaper than the potential cost of employing a full-time government detective agency. After Arizona’s territorial governor offered a reward for the capture of murderers, an 1872 edition of the Arizona Sentinel wrote that:

Thus, it will be seen at a glance that Gov. Safford intends to protect the lives and interests of the people of Arizona so far as is in his power. He is deserving of much praise for the manner in which he proposes to put a stop to murders and depredations being committed within the territory.

As such, bounties and private detectives brought many outlaws to justice. In 1883, Wells Fargo detective James B. Hume, with the help of another private detective, Harry Morse, captured the notorious stage robber Black Bart, who had robbed 28 Wells Fargo stagecoaches. In another instance, Robert Ford, a member of the infamous James-Younger Gang, killed Jesse James seeking a large reward funded by railroad companies, as recounted by historian T.J. Stiles.

While bounties and private detectives may seem like relics of the past, they offer valuable insights into how markets fill in the gaps when the government fails. Crime victims and public officials, seeing opportunities to benefit, whether that be from restitution, deterrence, or some other benefit, put out bounties for fugitives, while profit-seeking bounty hunters came to their aid. Such an example should spur us to reconsider how we handle criminal justice in modern America.

Although the frontier is long gone, private law enforcement remains the backbone of law enforcement even today. As it stands, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are nearly 50 percent more private security guards than government police. Bail bondsmen and enforcement agents play a critical role in ensuring defendants appear at trial. Meanwhile, numerous private firms supply home security systems and cybersecurity services. Like any other good or service, individuals demand security and law enforcement.

As many have called for criminal justice reform in recent years, it’s worth remembering America’s long tradition of market solutions to law enforcement, which reminds us that justice need not come from a shiny badge.