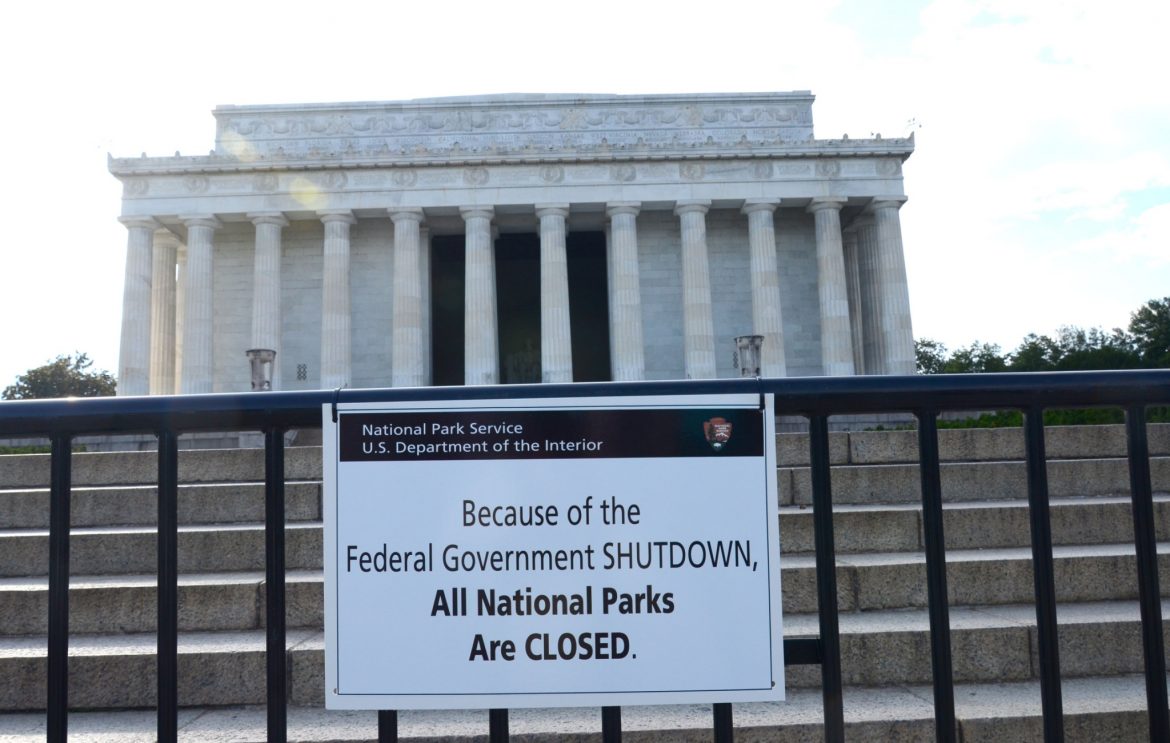

Government is presently “shut down” for failure of Congress to pass a budget for the start of the fiscal year. It is a relatively rare event, having happened just 21 times previously. Thus, politicians and pundits are presently telling us what to make of it: identifying immediate impacts, foretelling enduring consequences, and measuring the macroeconomics.

There are just two ways out of this shutdown: approval of a full Fiscal Year 2026 budget or the more easily accomplished interim “stopgap” budget called a “continuing resolution” (CR). As pressure mounts for the easy fix, it is time to hear the truth: CRs can be worse than shutdowns.

Shutdowns Are Not All That

There will be thousands of genuine stories of hardship and frustration that will emerge from this shutdown. There will be waste, interruptions, and inefficiency. Still, from a whole-of-society perspective, shutdowns have historically been much ado about little. Government is not shut and it is usually only moderately and briefly down.

Several myths about shutdowns prevail which make them seem dire. First: government must cease spending. In truth, spending may continue, first, with residual funds from prior years (e.g., research and development, procurement of large items, and working capital operations); and second, when required or implied by law (e.g., Social Security).

Another myth: government must cease activity. In truth, the government may conduct activity deemed essential. The result is that about 75 percent of all federal employees continue to go to work. And there they are met by a large contractor workforce. Contracts, which amount to about 47 percent of all discretionary spending, will have had lengthy periods of performance funded with last year’s budget — for moments just like this.

A final common myth: the economy suffers. In truth, while GDP does fall during a shutdown, government plays ready catch up after a shutdown. Plans swish from one month to another. When all is said and done, macroeconomic indicators will show nary a blip in the data.

The only truly unsettling predictable and regular impact is to federal employees. Whether working or furloughed, they cannot get paid for these days of shutdown until a resolution. That is indeed unfortunate.

When Washington’s Quick Fix Becomes a Slow Bleed

A CR avoids a shutdown. It grants an interim budget — one that mirrors last year’s spend rate and plan. It basically says, “Keep calm and carry on like last year!”

A CR seems like a commendable fix. However, the effects on one governmental function, the military, expose the many problems.

The first problem is that we do not live in a static world. Right out of the gate, inflation and additional sectoral price growth take a roughly 4 percent chunk out of last year’s spending power.

Then misalignment of plans quickly emerges. Each year, as the military adapts to new threats, they plan for hundreds of different acquisition and construction projects as well as various increases and decreases in production. During a CR, these changes are forbidden. Money-in-hand (usually about 6 percent) ends up sitting idle during a CR.

Unfortunately, catch up is not readily feasible as it is after shutdowns. CRs occur almost every year and last on average over a third of a year. With such recurring delays, the integrated coordination of complex projects falls apart: submarines come to dry dock and leave without updates, aircraft get built but cannot securely communicate with each other, and launch windows open and close for a satellite that is not ready.

At the end of the year, the military often is left maintaining an island of misfit toys, while the future of warfare remains just over the horizon.

Fiscal Uncertainty Promotes Waste

CRs introduce uncertainties as to what may be purchased and when the CR will be superseded by an actual budget. Uncertainties change organizational behavior in deleterious ways.

Starting at the Treasury, each level of authority becomes protective of its funds. Managers parcel out money to lower organizations the way survivors on a life raft parcel out morsels of food.

Between price growth, restrictions on change of plans, and an organizational possessiveness that would make Gollum blush, spend rates for lower-level program offices often fall to 75 to 80 percent of last year’s.

Tough decisions about priorities must happen: hiring slows, training is put on hold, military moves are held off, and leaders get pitted against each other.

In this environment, financial managers repeatedly must justify short-term spend plans and execution performance. To avoid money being clawed away, they spend expediently instead of necessarily effectively. Small-batch purchases replace the harder but more efficient large-batch purchases; the immediate gets preference over the optimal.

Similarly, contracting officers must repeatedly let contracts with small periods of performance. Because of the churn, they tend to choose contract types based on simplicity of execution instead of effectiveness.

When a full budget does arrive, yet more trouble occurs. Financial managers race with their belated windfall into frenzied end-of-the-year spending, often on low-value items.

A lengthy CR (as occurs in most years) undermines plans and produces many colors of waste.

Stopgaps and Jacklegs: Euphemism for Failure

A continuing resolution is commonly called a “stopgap.” But is “stopgap” an appropriate term?

Modern dictionaries define stopgap as a “temporary expedient,” a solution “until something better or more suitable can be found.” Etymological dictionaries trace it to the literal plugging up of openings — dikes, hedgerows, and shield walls used against restless seas, impertinent cattle, and bloodthirsty Vikings.

Calling a CR a stopgap makes it seem a commendable act. But in truth, CRs are applied too frequently and lengthily. As a result, they swamp the land year after year, leaving it salted. This swamping, no doubt, does more damage than the brief political theater of shutdowns

The public should start to stigmatize CRs. To that end, I propose a different metaphor for a CR. I suggest we dig up an old slang word of American origin, an “Americanism” suited to this uniquely American malpractice. I suggest we call a CR a “jackleg.” A jackleg is a temporary fix like a stopgap, but it is a fraudulent one from those who are “incompetent, unskillful, or dishonest.”

Congress’s License to Miss Deadlines

Each year, Congress has from February to October (about the length of time of the gestation of a human being) for its members to agree on terms. Nearly every year they fail.

A CR came about as an invention by Congress. It is their self-approved license to fail at the constitutional duty granted them. For such an insidious invention, a “jackleg” is perhaps the only appropriate epithet.

The public should demand that Congress does its job and passes a budget by October 1 each year. If it cannot, there should be only one tolerable outcome — the embarrassment of a shutdown instead of the illusions and deceptions of jacklegs.