I wrote a few weeks ago about how Trump’s manipulation of the Federal Reserve would have to go much further to achieve his goals. Lower interest rates can stimulate the economy because a lower cost of borrowing can increase investment and spending. Trump has also been pressuring the Fed to lower its target, so that mortgage interest rates and car loan interest rates fall.

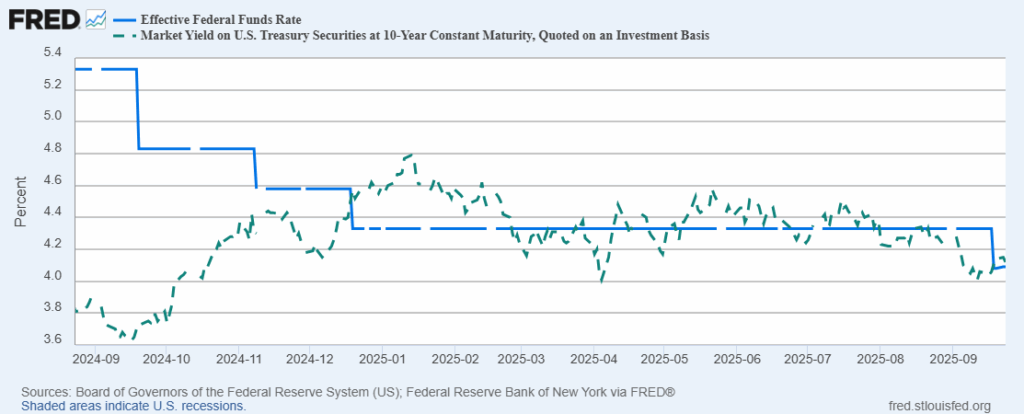

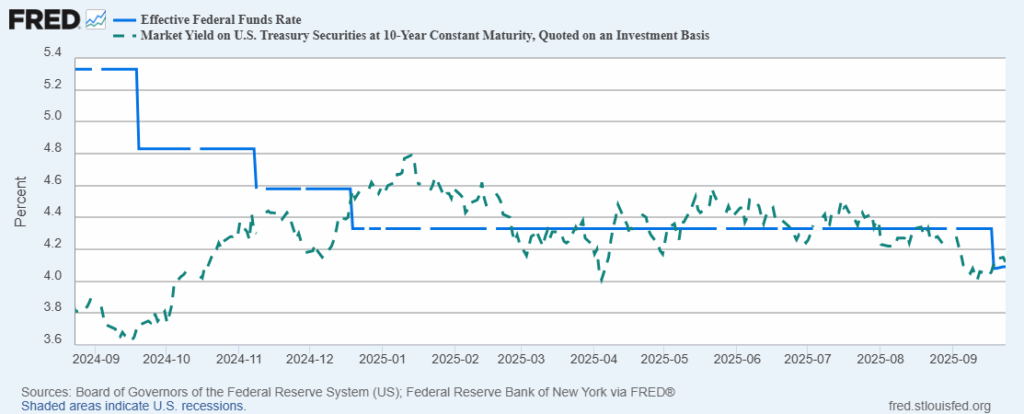

Many people consider the federal funds rate (an overnight interest rate) targeted by the Federal Reserve to be a proxy for economic stimulus: lower Fed funds rate = more investment and more home and car purchases. Reality, it turns out, is far more complicated. Consider Figure 1 comparing the 10-year Treasury rate with the federal funds rate (FFR) since the Fed began lowering its target last fall:

Figure 1

While the federal funds rate (FFR) has fallen by over 1 percent from 5.3 percent to about 4.1 percent. The 10-year Treasury rate, has risen nearly half a percent from 3.8 percent to about 4.2 percent. Not only did the rates not move in the same direction, they moved in opposite directions!

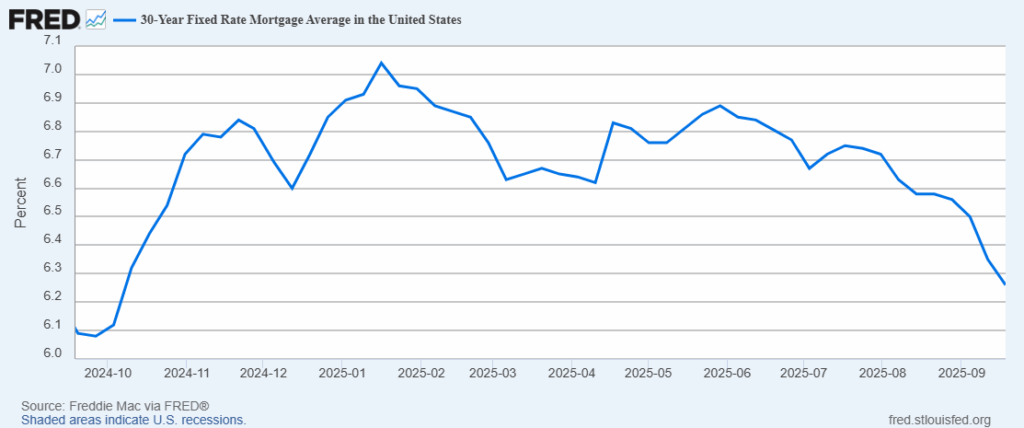

This matters because mortgage rates are based on the 10-year interest rate, not the FFR. So it should come as no surprise that the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate, 6.2 percent, is slightly higher than it was a year ago and was elevated most of the last 12 months (Figure 2).

Figure 2

So why is the 10-year rate not falling as the Fed reduces the FFR? It’s because the 10-year is set by the market, by the supply and demand for the instrument, while the Fed determines the FFR by changing how much interest it pays banks and what discount rate it offers banks.

The big story in the 10-year Treasury market is an ever-expanding supply of 10-year bonds, which puts downward pressure on the price of those bonds and thereby upward pressure on their yield/interest rate. For example, you earn more interest when you can pay $900 for a bond that will pay you $1,000 in five years than if you have to pay $950 for it.

The federal debt has grown rapidly over the past 25 years from $5.6 trillion at the beginning of 2000 to $12.3 trillion in 2010 to $23.2 trillion in 2020 to $36.1 trillion at the beginning of 2025. This is the result of chronic annual deficit spending, which ballooned during COVID and has remained elevated ever since:

- FY 2019: $984 billion

- FY 2020: $3.1 trillion

- FY 2021: $2.8 trillion

- FY 2022: $1.4 trillion

- FY 2023: $1.7 trillion

- FY 2024: $1.83 trillion

Existing debt is refinanced through the issuance of new Treasury bonds. And annual deficits are financed by issuing new Treasury bonds. The growing supply of Treasury bonds has been keeping the 10-year rate high, even when the short-term FFR has been falling.

Meaningful change in the 10-year, and thereby in mortgage and auto loan interest rates, can come either by fiscal responsibility at the federal level, or by much more active (and distortive) Fed actions of printing money and buying 10-year Treasury bonds. While this would certainly put downward pressure on the 10-year yield in the short run, such a policy is self-defeating over time because it creates inflationary pressure. And as inflation increases, the nominal interest rate demanded by investors also rises.

Of course, the Fed could step in again to buy more bonds with more newly created money, but then the inflationary pressures get even worse. Also, in the short run of such monetary expansion and artificial repression of interest rates, economic activity will temporarily surge due to the stimulus. But when inflation (rising prices) appears, many investment decisions will be revealed to be unrealistic and unsustainable.

This is why AIER scholars, and many others, argue for Fed independence rather than a politically directed Fed. Politicians have never managed money creation well. Inflation, and sometimes hyperinflation, can be seen in ancient Rome, in medieval Europe, in the Revolutionary and Civil War periods, in the Weimar Republic, in Zimbabwe and Venezuela, and in many other times and places.

Fed independence does not mean Fed officials can’t or shouldn’t be held accountable. Congress authorized the Fed and gave it a dual mandate of maintaining stable prices and maximum employment. While Congress should ask Fed officials hard questions, the dual mandate inhibits their ability to hold the Fed to account.

For example, was the Fed wrong to lower its target FFR in September? Given that its target inflation rate is 2 percent and the most recent print in August was 2.9 percent, it seems like the Fed made the wrong decision. However, given the weakening in the job market, the Fed’s mandate to maintain maximum employment suggests that they may have made the right decision. How can an institution be held accountable when its mandates sometimes conflict with each other?

Rather than letting Trump reshape the Fed and direct it toward his short-term political goals, Congress should take the reins and replace the dual mandate with a single mandate of price stability. And if Congress wants to reduce the interest rate people pay for mortgages and car loans, and the interest rate the federal government pays on its debt, they have to cut spending anywhere and everywhere they can.

This government shutdown doesn’t fix the problem. Nor does a “clean” continuing resolution. Leaders in Congress need to get serious about trimming the federal budget. The Federal Reserve can’t do it for them.