Capitalism as an ideology is on the ropes, especially among young people. A troubling 2025 Cato survey found that 62 percent of young Americans (age 18-29) hold a “favorable view” of socialism. Thirty-four percent even hold a favorable view of communism.

I’m skeptical that these numbers represent a considered economic analysis or a deeply thought-out support of the ideology (communism) that killed over 100 million people in the twentieth century. Instead, I think what’s going on is that young Americans are picking up on the fact that there’s something broken about our current system, which they label “capitalism”, and that’s leading them to the maximally oppositional stance. It’s a sort of “anywhere but here” economic analysis.

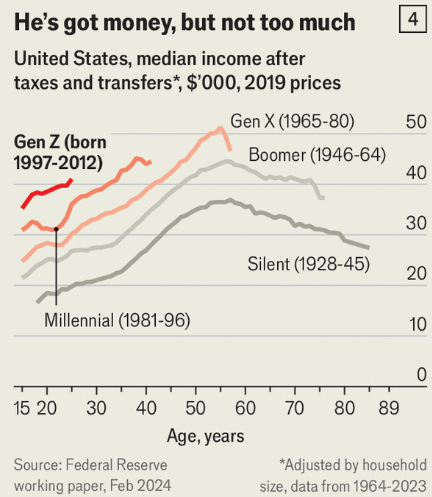

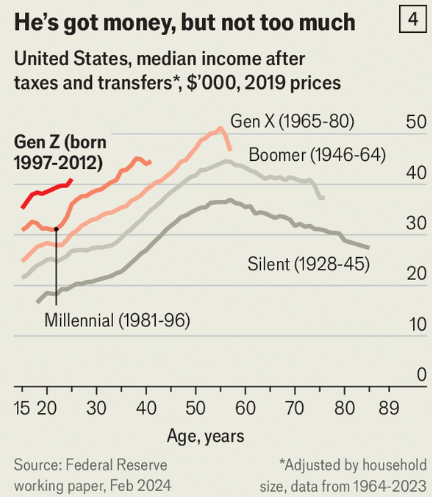

Economists and libertarians are fond of responding to young people’s opposition to capitalism by arguing that said opposition is silly: according to traditional economic measures, young people have never had it so good. A report by The Economist, for instance, notes that Gen Z earns substantially more (even adjusted for inflation) than did members of any previous generation at their age:

Most young people have access to technology that surpasses anything a billionaire could have purchased even twenty years ago.

So what’s going on? Why don’t young Americans like capitalism? I think the problem is that our modern society is broken in ways that don’t show up in traditional economic metrics.

In You Are Not Your Own, professor Alan Noble describes a phenomenon called “zoochosis”: it’s the combination of anxiety and boredom that afflicts zoo animals due to the fact that they spend their lives in an environment for which they weren’t designed. Zoochosis is a portmanteau of “zoo” and “psychosis”, and quite literally suggests that “these are animals driven to psychosis from being in captivity.”

Noble suggests that the United States has its own form of zoochosis. We’ve built a society that’s marvelous in so many ways, but that in others runs contrary to our human natures. As a result, he argues, we’re now living in a world for which we weren’t designed — and, like zoo animals, we’re suffering the consequences. That, for Noble, is the primary explanation for why and how modern society doesn’t work.

Let’s look at a few examples of how Noble says that modern society fails us.

First, a lot of us are always working. Work follows us home in ways that it never did for our grandparents. Because work is on our devices, many of us find that our dinners with our families or our time playing with our children is interrupted by seemingly-urgent messages from the office. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 30 percent of full-time employed people — roughly 40 million — work on weekends. Some of that is delivery drivers or service workers who don’t work a typical Monday-Friday week, but a lot is white-collar workers who are expected to be on call 24/7.

The fact is that we weren’t made to be on 24/7. We were made for natural rhythms of rest. We were made to have downtime and uninterrupted time with our families. Our parents and grandparents describe jobs to which they worked hard at the office and then clocked out and went home, which sounds both strange and paradisiacal to young Americans who are used to getting evening and weekend emails from their bosses. Is it any wonder that these young folks have soured on the economic system that they see as the cause of their long hours and frequent burnout?

Our modern society also encourages us to live online. As the Internet has exploded to take over our lives, it’s sometimes hard to remember that even 20 years ago, life for the average American looked very different. We socialized in person. We saw the same relatively small group of people day-in and day-out. When we needed to buy something, we had to go to a store and interact with other human beings. Most of our work time, and most of our leisure time, was spent in relationship with other people.

Life today looks completely different.

In 2023, 35 percent of us did some or all of our work from home, and 13.8 percent of us “usually” worked from home. If we need to buy something, we’re more likely to interface with a computer screen than with a human being at a brick-and-mortar store. Over half of teens spend an average of 7 hours and 22 minutes per day online, which for the most part is time they’re not spending on in-person interactions.

As wonderful as the technology behind our move to life online is, and as profoundly helpful as it’s been to many people (FaceTime lets me video chat with my parents every week), there’s something about the sudden move to life online that runs contrary to our nature. We’re like caged lions living in a zoo — fat, well-cared-for, but unable to escape the gnawing sense that we were made for an environment very different from the one in which we live.

It’s perhaps understandable that young people would blame capitalism for their zoochosis. After all, if our lives feel harried and anxious and lonely, it makes sense to criticize the dominant system in which we live. But while this impulse is understandable, I don’t think it’s correct.

Capitalism is essentially a big and empty box. As consumers and as producers, we can exert our market power to fill that box with whatever we desire. So far this century, we’ve been filling that box with social media apps, with remote work, and with remote shopping, all of which lead to both endless work and to life lived online. But we could just as easily choose to fill the box with other things.

Instead of endless work, we could use our market power as producers of labor to enact polite but firm boundaries on our work life. We could tell bosses that we’re happy to grind Monday through Friday during normal work hours, but that we’re not available on nights or weekends unless the building is on fire. If enough of us imposed boundaries like this, then market conditions would change and a culture of always-on work would be replaced by a more traditional work-life balance.

The beauty of free markets is that they give us exactly what we ask for. For the past few decades, what we’ve asked for has led to a broken society in which millions of people feel anxious, depressed, and lonely. But it’s unfair to blame capitalism for this, because we chose it. We chose it every time we spent time on Facebook instead of being with friends in the real world, every time we binge-watched Netflix instead of going outside, every time we accepted higher salaries at the cost of being on-call for our jobs 24/7.

If we want to restore faith in markets, we have to use our power as market actors to build a society that works for us.