About 10 years ago, economist Matthew Mitchell and the Mercatus Center published a short video titled “The Wrath of CON: How Certificate-of-Need Laws Affect Access to Health Care.” The video described certificate-of-need (CON) laws, an obscure niche in healthcare policy known best by a handful of policy wonks and healthcare professionals, and the barriers CON laws create.

Under the video’s humor lay a dark truth: CON laws hurt patients and providers at their outset and the laws’ continued existence compounds that harm. Repealing CON laws can help improve access and affordability in healthcare.

Fortunately, over the past decade, many states have moved to reform or repeal their respective CON laws. However, there is still much progress to be made. Mitchell’s 2024 paper, “Certificate of Need Laws in Health Care: Past, Present, and Future” and a 2025 review of academic literature from economists Charles J. Courtemanche and Joseph Garuccio provide updates on CON laws and guidance for future research and policy.

What is CON?

Certificate-of-Need (CON) laws require the approval of states’ health planning agencies for health care providers to engage in regulated actions such as opening or expanding facilities or purchasing equipment. Additionally, in many states with CON regulations, the decision to grant a CON is made by a board whose members may work for incumbent providers. This is sometimes referred to as a “competitor’s veto.” Mitchell also notes that in all but six CON states, incumbent providers are allowed to participate in the process and object to the application of a would-be competitor and often use the objection as leverage against the potential competitor from encroaching on their territory. Mitchell calls it “a type of territorial collusion that would be a per se violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act were it not facilitated by the state.”

CON laws were first applied to healthcare by New York State in 1964, and by 1970, 25 additional states had similar regulations. In 1974, Congress passed the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRDA), where the federal government threatened states into adopting CON regulations by saying they would withhold federal funding for healthcare for any state without CON laws.

The desire to push CON came from a misguided belief that such regulations could, in Mithcell’s words, “cause hospitals to acquire fewer beds, fill them with fewer patients, and therefore spend less money.”

The threats to withhold federal funding never materialized, but by the early 1980s every state had a CON program for healthcare. As Medicare reimbursement switched from retrospective (hospitals get paid whatever they spend with little incentive to control costs) to prospective reimbursement (hospitals are paid a fixed, predetermined amount for services), CON policies were reexamined.

Finding that CON laws did little to control costs, especially under prospective reimbursement, policymakers in DC rolled back CON requirements. While the federal CON requirements were repealed, most states maintained CON regulations, which led to greater variation among state CON regulations. By 1990, eleven states had followed suit and repealed CON laws, with only Wisconsin reinstating the program. By 2000, Indiana, North Dakota, and Pennsylvania had repealed most CON laws. 2000 Wisconsin has since re-repealed its CON regulations. In 2016, New Hampshire was the last state to fully repeal CON.

In their 2025 review of the academic literature on CON, Courtemanche and Garuccio find “in at least some cases, CON laws restrict both entry of new competitors and expansion of existing hospitals. The reduction in competitors increases the number of procedures in hospitals.” They continue by noting such findings provide

“[L]ittle evidence that this translates to increased prices or higher hospital profitability, and hardly any research tests for reduced closure rates. Studies on hospital efficiency and quality of care for procedures performed exclusively at hospitals mostly point to null or negative effects, but evidence on quality is more favorable for services that can be provided outside of hospitals.”

While there may be other factors at play (such as government subsidies, the Affordable Care Act implementation, or the variation of CON laws among states), costs can still be passed onto patients without changing prices. Higher costs may look like longer wait times (whether in a hospital or fewer scheduling options), staffing shortages, or the opportunity cost of patients traveling to see a specialist either on the other side of their state or in other states.

If one thing is clear, CON regulations have failed to deliver on the promise of affordable and accessible healthcare.

Mitchell’s Findings on State Experiments with CON Reform

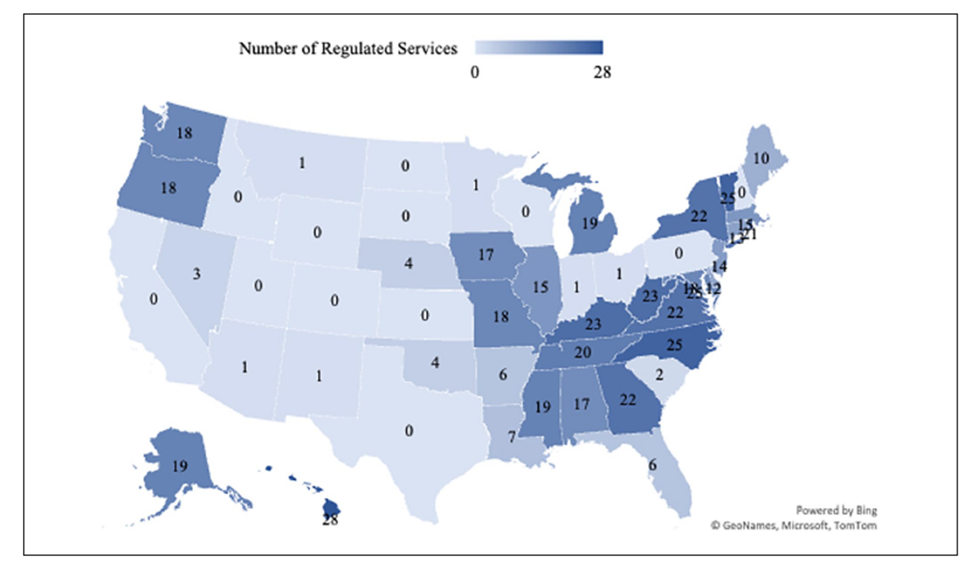

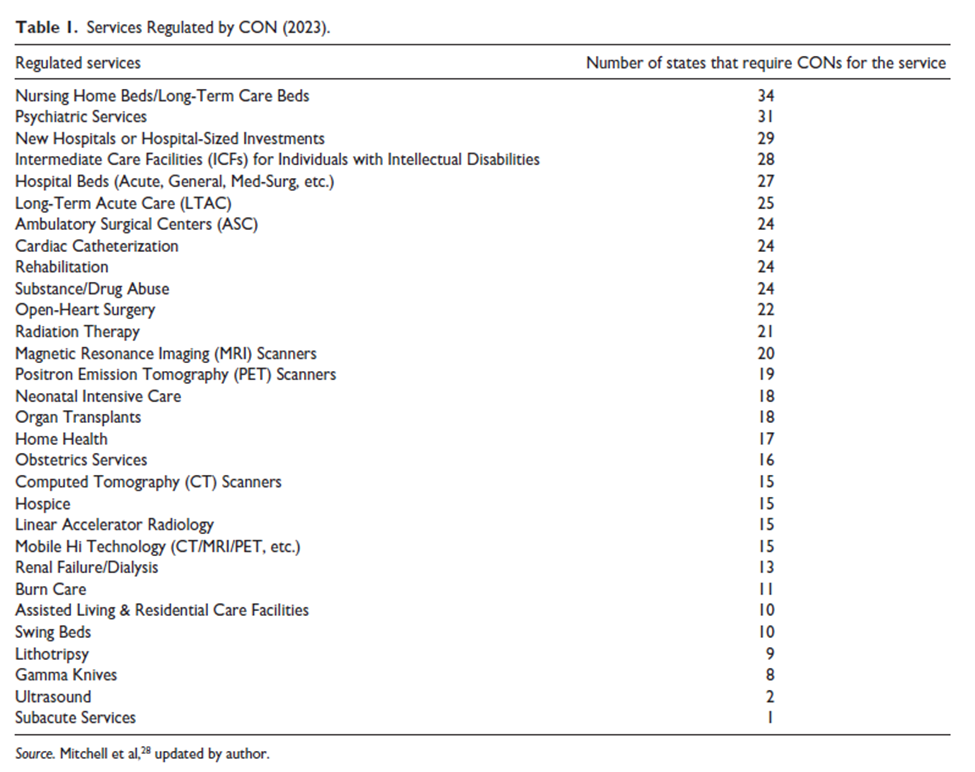

As of December 2025, 15 states have fully repealed CON regulations. Additionally, numerous states have reformed their CON regulations to shrink the healthcare services that require a CON. Mitchell’s map is reprinted as Figure 1 and table is reprinted as Table 1.

Figure 1. Number of Health Care Services in Which a CON is Required (2023)

Figure 1 summarizes the number of health care services subject to CON regulation while Table 1 identifies the services most commonly regulated. Arizona, Minnesota, and New Mexico limit CON requirements to ambulatory services while Indiana, Ohio, and South Carolina (as of 2025) only apply CONs to nursing homes. Hawaii regulates the most activities, requiring CON approval for 28 services and technologies. Mitchell finds that nursing home beds are the most frequently regulated, followed by psychiatric services, new hospitals, and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Investment thresholds triggering CON review vary from state to state and are generally lower for non-hospital providers (a $3 million expenditure trigger for ambulatory services in Maine) than for hospitals (excess of $12.365 million in capital expenditures in Maine).

From Mitchell’s findings and his survey of the academic literature, he finds that CON laws are generally associated with high variable costs in general acute hospitals, fewer available hospitals, higher Medicaid costs for at-home care and long-term care, and higher health expenditures. The more stringent and numerous the CON laws in the state, the worse access and affordability for healthcare.

In states that did repeal CON laws, Mitchell found that hospital charges in states without CON are 5.5 percent lower five years after CON repeal. Additionally, safety-net hospitals in states without CON had higher margins than similar hospitals in states with regulation. While repealing or reforming CON will not fix all healthcare policy challenges, doing so can help increase affordability and healthcare access.

What Comes Next?

As Mitchell’s map shows, many states have the opportunity to reform and repeal CON to their betterment. States such as West Virginia (one of the most stringent CON states) have residents that seek healthcare in neighboring states like Pennsylvania (0 CON regulations) because there is greater access to care outside of the state.

To this end, there are a myriad of options for CON reform. Aside from a full immediate repeal or a regulatory sunset provision, state policymakers can also eliminate the competitor’s veto.

Preventing incumbent providers from participating in the CON review process (including requesting hearings and appeals) can help reduce cronyism in the CON application process. Increasing transparency in the CON application process and CON laws can also help reduce cronyism as well.

Americans are strained by the cost of healthcare. Reforming CON laws can help alleviate some of that strain. A full repeal can provide even greater help.