“Free” parking has a huge cost. That’s the message that UCLA planning professor Donald Shoup, who died last week, took to the world. He lived to see his research gain credibility and influence, bit by bit, until just a few years ago a nationwide parking reform movement burst onto the scene and started winning policy victories.

Shoup was trained as an engineer and an economist, but he made his mark in urban planning, which he taught at UCLA for over four decades. He is best known for his 2005 book, The High Cost of Free Parking, published when he was 66 years old.

In that book, Shoup points out that city parking is often allocated free of charge at point of use. “Free” parking has real costs, though. Because there’s no charge, drivers demand too much of it. In particular, they demand too much of it at the wrong places at the wrong times.

Suppose you want to run into a bagel shop on your way to work. You don’t need to park there for long, but you highly value having a nearby parking spot so that you can run into the shop, run out with your bagel, and be on your way. The only problem is that there might not be any spot for you, because the lack of a price might lead other drivers to leave their car for long periods of time.

This is precisely what happened when the automobile became a mass consumer good, says Shoup. Drivers couldn’t find places to park, and planners’ response was to require developers of buildings to include parking proportionate to the buildings’ use. The parking minimum was born.

It was a cure worse than the disease, says Shoup. Like “lead therapy” recommended by eighteenth-century physicians, parking minimums poisoned the city. “Free parking increases the demand for cars, and more cars increase traffic congestion, air pollution, and energy consumption,” he writes. “More traffic congestion in turn spurs the search for more local remedies, such as street widenings, more freeways, and even higher parking requirements.” Cities were turned over the automobile and became danger zones for pedestrians and cyclists.

To these ills, Shoup adds the effects of parking minimums on the cost of development. These costs are paid by property owners initially and then passed on to tenants, both residential and commercial, and ultimately show up in the costs of all locally produced goods and services.

Shoup meticulously goes through study after study of how the introduction of parking requirements affected development. In Oakland, parking minimums drove up the cost of building apartments, significantly reduced the number of apartments built, and reduced land value per acre. That meant in turn that more of the property tax burden had to be shouldered by other residents of the city. The same dynamic played out with single-family housing in San Francisco, office development in southern California, apartments in Los Angeles, and apartments in Palo Alto, to name just a few studies he reviews in one section of the book.

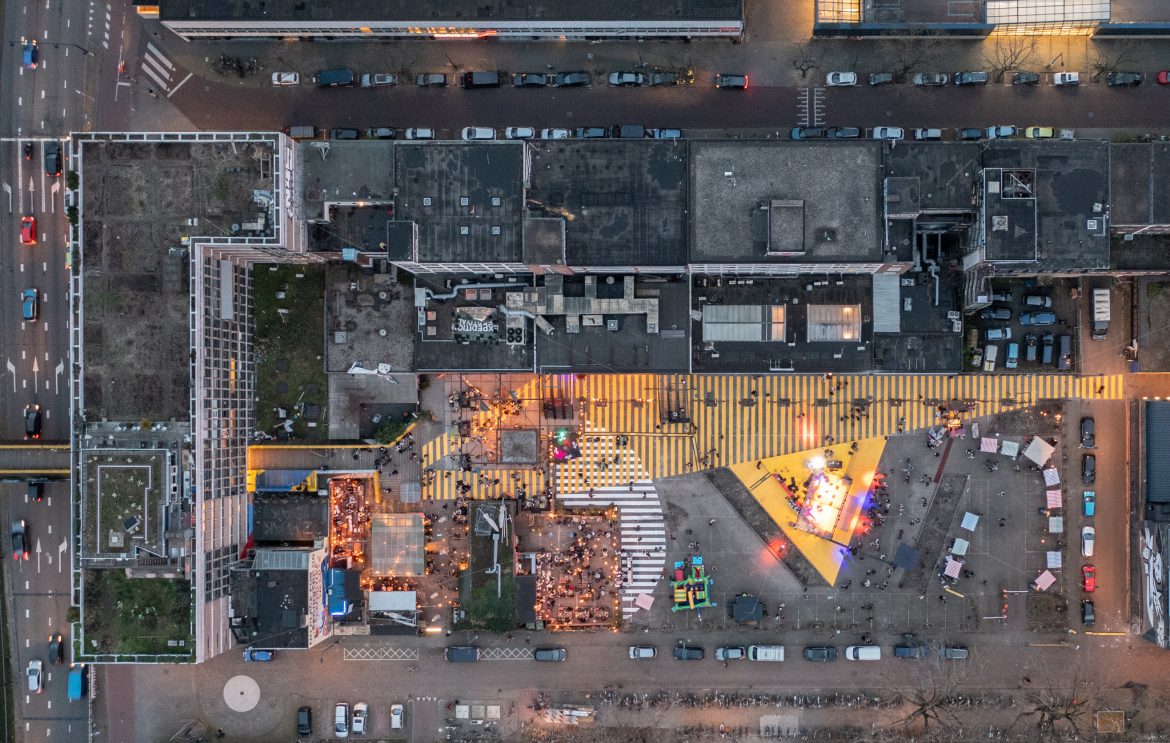

Shoup notes the aesthetic and environmental costs of surface off-street parking lots too. Air pollution comes from drivers circling for parking. Water pollution comes from pavement runoff. Surface lots are ugly and uncomfortable: hot in summer, cold in winter, and always windy. He even advocates placing limits on off-street parking, perhaps taxing it and shunting it to the urban periphery, as Carmel, Indiana does.

Even if we don’t go that far with him, he persuasively argues that instead of mandating free parking, cities should charge market prices for on-street parking. Shoup pioneered technologies to adjust the price of parking in real time to ensure that there are always spots available on every block. The new revenues from charging for parking could be used to improve infrastructure in the area, building public support for the new market. Experimental deployments of the technology showed that they worked to keep parking available for those who urgently needed it. While there is an upfront cost to deploy the technology, cities across the country are gradually adopting it.

Today, the Parking Reform Network advocates Shoup’s ideas of abolishing minimum parking requirements and charging market prices for on-street parking. Thanks in part to their efforts, 99 places in eight countries have since abolished all parking minimums. (New Hampshire could be the first state to do so.)

Unfortunately, decades of misregulation have scarred our cities. In many medium-sized cities, off-street parking lots make up more than a third of the land area in downtown (Albuquerque, Fresno, Little Rock, Orlando, and Arlington, Texas are examples). Most major cities have lost human-scale neighborhoods and classic architecture to pavement as a result of urban renewal and zoning. You can see photos of this change in Denver here.

That’s just to say that the modern parking reform hasn’t arrived on the scene a moment too soon. We have Donald Shoup’s work to thank for opening so many people’s eyes to how central planning wreaks havoc even at the level of the humble parking space. Now, let’s take back our cities.