I hadn’t thought of Follies and Fallacies in Medicine for years, but it caught my eye at an auspicious time. The book, written by doctors Petr Skrabenk and James McCormick, opens with a story on what a British medical journal described as the latest trend in medicine: clinics injecting patients with horse blood and pig embryos to “boost people’s energy and restore virility.”

The authors made it clear they saw these treatments as a modern version of snake oil, but the practice was quite lucrative. The clinical specialist, who drove a BMW and had recently purchased “a large house in a fashionable neighborhood,” was charging £1,500 a pop ($6,500 USD in 2024).

“The history of medicine is full of similar and equally extraordinary events,” write Skrabenk and McCormick.

Their book, which was written in 1990, goes on to explore “why otherwise rational people” put their faith in bad science and junk medical procedures.

COVID Madness, Five Years Later

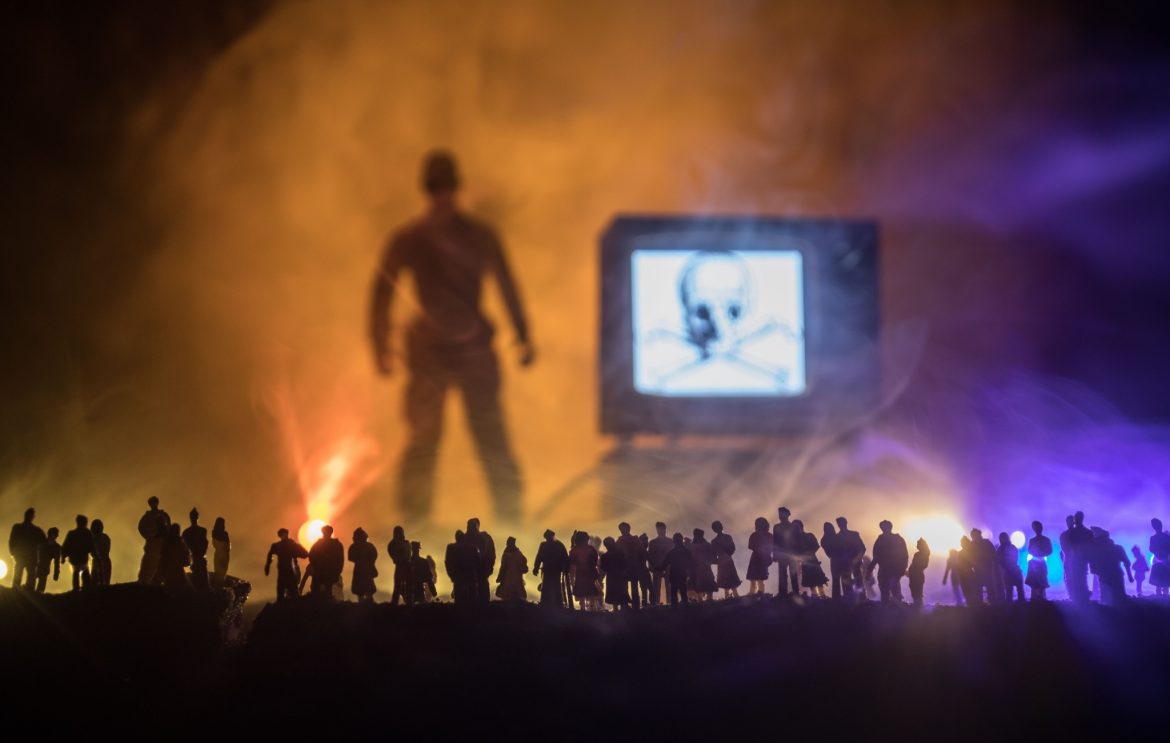

We are approaching the five-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period that saw governments around the world shut down economies and embrace authoritarian policies in the name of public health and The Science. It was Hayek’s fatal conceit played out before our eyes.

Economic hubris, bad science, and raw state power unleashed a period of madness. It wasn’t just that the state’s non-pharmaceutical interventions didn’t work. They often didn’t even make sense.

“Non-essential” businesses were closed, but liquor stores were left open. Politicians ignored their own orders. Masks were required in restaurants when you walked to your table, but could be removed once you were seated. Wrestlers were allowed to wrestle, but were prohibited from shaking hands. Children, who were all but impervious to the virus, were banned from playgrounds, even though there was no evidence of outdoor transmission.

The list goes on. Many policies continued well into 2021, even though it had become clear they were damaging and ineffective (though they were temporarily suspended in May 2020 to accommodate social justice protesters).

The damage of these policies will be felt for decades, and we know today the reason they were so ineffective: many of the government’s COVID policies weren’t even based on science.

To offer but one example, consider “social distancing” — the rule that required people to stay six feet apart in public. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the architect of the US government’s COVID response, acknowledged to lawmakers in sworn testimony in 2024 that the guideline “sort of just appeared” without a solid scientific foundation.

In their book, written thirty years before the arrival of COVID-19, Skrabenk and McCormick identify a slew of fallacies that pollute the field of science. The authors aren’t talking about intentional deceit, fraud, or misinformation, but erroneous reasoning.

One stood out to me above all others: The Fallacy of Authority.

‘It Must Be True, the Lancet Published It’

Many of the scientific fallacies the authors describe can be identified during the COVID pandemic, but it was the Fallacy of Authority that reigned supreme during the period. The authors describe it as the idea that something is true because it came from an authoritative source.

“It must be true because I read it in the paper, saw it on television, the surgeon said so, the Lancet published it,” Skrabenk and McCormick write.

The fallacy is persistent in science and medicine because respect for authority underpins scientific inquiry and education. The authors explain that it’s customary for students, who memorize vast quantities of information, to fall pretty to the mistaken belief that what they are reading is “truth,” particularly when the source is authoritative. Challenging the status quo becomes difficult even for bright, independent-minded thinkers.

This baked-in respect for authority helps explain why so many of the greatest scientific breakthroughs were initially met with skepticism.

Skrabenk and McCormick point out that scientists initially sneered at William Harvey when he published his work on blood circulation. Hans Krebs and Enrico Fermi both won Nobel Prizes, but their research on citric acid cycles and beta-decay was first rejected by Nature.

“There are good reasons for distrusting the opinion of authority, not only in medicine but in science proper,” Skrabenk and McCormick observed.

The authors do not advocate intellectual anarchy. But their point about questioning science and those in authority was clear.

“We should be kind to all people, even those who are vested with authority,” they wrote, “but we must be ruthless in seeking and criticizing the evidence on which their beliefs are founded.”

One Fallacy to Rule Them All

Dr. Fauci saw things differently. When public blowback began to gain momentum in early 2021, Fauci responded with indignance.

“Attacks on me, quite frankly, are attacks on science,” Fauci said. “All of the things I have spoken about, consistently, from the very beginning, have been fundamentally based on science.”

This statement was not true, as Fauci’s own statements later made clear. But even worse, Fauci was treating criticism of his policies as attacks on science.

In a sense, Fauci was embracing the Fallacy of Authority, and it was a strategy adopted by others.

CNN host Brian Stelter ran segments mocking people who did “their own research,” comparing them to QAnon conspiracy theorists. “Follow the science” became a popular rallying cry, a phrase that the Washington Post noted often simply meant “follow the scientists.”

The mantra, which embodied the Fallacy of Authority, runs counter to the very ethos of science, which is not a person or a group of people

Science is a process, the methodical study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world.

“There isn’t a thing called ‘the science,’” Michael D. Gordin, a historian of science at Princeton, told the Post in a deep-dive story on the phrase. “There are multiple sciences with active disagreements with each other. Science isn’t static.”

Gordin is correct. During the pandemic, people on all sides of the COVID debate argued “The Science” was on their side.

For example, the Food and Drug Administration said ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug often used to treat humans for tropical diseases, should not be used as a COVID treatment. Doctors across the country were prescribing the drug, but critics of the treatment were mocking it because ivermectin is also used on livestock.

“You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Serious y’all. Stop It,” the FDA tweeted.

The tweet, which generated more than 106,000 likes before it was deleted, was a response to Joe Rogan, who had posted a video during his COVID recovery praising ivermectin.

Yet those who took the off-label drug were also quick to claim the authority of science was on their side.

“Even people who took a horse tranquilizer when they got COVID-19 were quick to note that the drug was created by a Nobel laureate,” Gordin told the Post.

While this author has no opinion on the efficacy of ivermectin as a COVID treatment, it was the FDA who was forced to settle a lawsuit in 2024 over its ivermectin posts.

The Purpose of Science

Five years later, it’s worth asking why the Fallacy of Authority exploded during the COVID years. The simplest answer, I think, is that everyone was arguing over public policy and everyone was seeking the best arguments. To make their case, people set out to find the most authoritative research that supported their views.

Though this helps explain the phenomenon, it’s not the best answer, or at least not a complete one. A better explanation for the explosion of the Fallacy of Authority is the growing influence of authorities in science.

In the twenty-first century, we’re increasingly asking science to do something it’s not designed to do and is incapable of doing.

The purpose of science inquiry. It’s a tool to help us understand the world in which we live, to expand human knowledge and explain natural phenomena. Giving orders does not fall within the realm of science. Indeed, as the economist Ludwig von Mises observed, science is woefully unequipped to tell us what we should do.

“[T]here is no such thing as a scientific ought,” Mises wrote, echoing the philosopher David Hume. “Science is competent to establish what is.”

This view of science is not held by everyone, particularly the state. During the pandemic, public health bureaucrats appeared as comfortable giving orders as making recommendations.

This invites an important question: what moral authority grants one the right to give orders to others?

The answer to this question has changed throughout history. Viking warlords were often given the power to command by their prowess in combat. The ancient Egyptians said their pharaohs were chosen by the gods. The moral authority of the modern bureaucratic state stems from The Science.

This arrangement of relative authority serves not just those in public health, but those in the private sector who cooperate with them. Albert Bourla, the CEO of Pfizer, was recently asked why vaccine makers need liability shields if their products are safe and effective.

“If the product is not safe and effective we’ll never get approval from the FDA,” Bourla answered.

Bourla didn’t present data or cite a study. He didn’t need to. The FDA’s authority was enough.

It was an answer that would have served just as well if the product he was offering (or mandating) was horse blood and pig embryos.