Joseph Schumpeter famously said that creative destruction is the “essential fact about capitalism.” Entrepreneurs are the moving force in Schumpeter’s drama, but they are victims as often as heroes. The reason is that having an idea is not enough; you have to make it work in the marketplace. The invention of ideas, and the fast borrowing of those ideas, reflect both the destruction and the creation of Schumpeter’s insight. Or, as Milton Friedman often said, capitalism is a system of profit and loss; the “and loss” part is important.

This truth is put in sharp relief by the story of the McDonald’s “Happy Meal,” a tale of innovation, theft, and Count Fangburger. In America, there are few childhood icons more deeply felt than the cheerful red box, branded toys, and child-sized portions, especially the (let’s be honest) French fries. But behind that cheerful cardboard is a real tale of creation, and destruction: RIP, Count Fangburger.

There are three narratives that one might deploy to explain the origins of the Happy Meal, and I’m going to present all three. The first begins in Guatemala in the mid-1970s; for some reason, this one has become dominant, perhaps because it smacks of the “colonial oppression” stories so popular in faculty lounges and hipster coffee shops.

The second, and more historically tenable, account begins with a rival fast-food chain called Burger Chef, which claimed (correctly) that McDonald’s had mimicked their packaging idea. The third, and even more correct, view holds that this kind of creative borrowing is a normal, even essential, part of capitalist creation, and destruction.

All three narratives are in some sense true, of course. But the real story of the Happy Meal is one of convergence, competition, and creative imitation — a tale as much about economics as about hamburgers.

Yolanda Fernández de Cofiño and the “Menú Ronald”

In 1974, Yolanda Fernández de Cofiño and her husband José María Cofiño acquired the first McDonald’s franchise in Guatemala, located in Zone 1 of Guatemala City. The Cofiños quickly noticed a problem: families visiting their restaurant often found that the standard McDonald’s portions were too large for their young children. Rather than simply shrink existing meals, Yolanda had a more creative solution.

“She created what she called the ‘Menú Ronald’ — a kid-sized meal with a small burger, fries, drink, a sundae, and a toy,” writes Katarina Hall in Reason magazine’s 2025 summer issue. Rather than wait for corporate approval, Fernández de Cofiño took matters into her own hands. She purchased small toys from local Guatemalan markets and packaged them in a child-friendly meal designed specifically for young customers. The innovation was not simply a smaller portion, but a tailored experience: food, fun, and a sense of being important.

This localized creation was an immediate success in Guatemala. But its influence would soon go much further. As Hall notes, the Menú Ronald “was not the product of a structured research team or marketing department, but of observation, care, and resourcefulness.” In time, word of its success made its way to McDonald’s corporate headquarters in the United States.

By the mid-1970s, McDonald’s was actively looking for ways to capture the attention of younger customers. Company executives had taken note of how breakfast cereal brands were marketing to kids through toys, mascots, and collectible items. When the seed of Fernández de Cofiño’s idea reached headquarters in Chicago, it landed in fertile ground, and sprouted into a corporate initiative in 1977, opening in a limited market (Kansas City), and then quickly spreading nationwide.

At least, that is the story McDonald’s tells the world. There is (record scratch!) another story.

Burger Chef: Creation, then Destruction

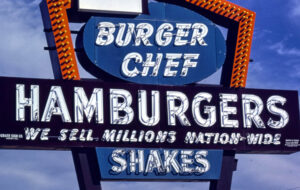

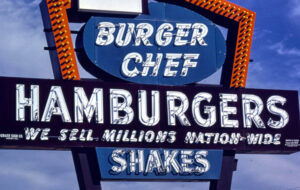

Burger Chef had been founded as a burger and fries restaurant, a rival of McDonald’s, in 1954. Headquartered in Indianapolis, founders Frank and Donald Thomas (no relation to Wendy’s Dave Thomas, though it’s a good story) had grown the Burger Chef franchise to more than 1,200 locations — second only to McDonald’s in the US. Burger Chef and McDonald’s were very aware of each other, and they were watching each other.

A big part of the reason for that watchfulness was that Burger Chef had always been an innovator. Years before McDonald’s introduced the Big Mac, Burger Chef had launched the Big Shef, a double-decker burger that one could describe as “two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, and cheese on a sesame seed bun.” It also developed an imaginative cast of cartoon mascots — including Burger Chef & Jeff, Count Fangburger, Burgerini the magician, Burgerilla the talking ape, and Cackleburger the witch — decades before the Ronald McDonald’s cartoon universe was developed into the McDonaldland characters.

But the biggest and most important marketing idea came in 1973: the Fun Meal, the first prepackaged meal specifically designed for children. The idea evolved from a 1972 offering called the “Funburger,” a child-sized portion, which featured a burger in puzzle-covered packaging and a small toy — two full years before Ms. Fernández had the same idea in Guatemala. The full Fun Meal launched a year later and included a hamburger, fries, drink, cookie, and a toy — all packaged in a colorful, game-filled box featuring Burger Chef’s cartoon characters.

This was not merely a meal; it was a branded, immersive experience. As The Indianapolis Star reported, the Fun Meal “transformed dinnertime into entertainment for children.” It became a defining feature of Burger Chef’s brand.

(Full disclosure: I was a night manager at a Burger Chef for two years, and I would estimate that I unboxed and folded more than 10,000 Fun Meal boxes during those evenings. I can personally attest that by the summer of 1977 Fun Meals were fully distributed at thousands of Burger Chefs nationwide, and were very popular for children, long before McDonald’s had Happy Meals. Furthermore, the “Works Bar,” a place where you could add lettuce, tomato, onions, pickles and other things to your burger, was a work of innovative genius.)

Of course, here comes McDonald’s: “Something something food for kids, something Guatemala….” Look, regardless of what Ms. Fernández de Cofiño did or didn’t do, the similarities between the Fun Meal and the “new” Happy Meal were impossible to ignore: a burger, fries, drink, toy, and a box decorated with puzzles, games, and cartoon characters. Sure, they were different cartoon characters, but this was clearly just corporate theft.

Burger Chef responded by filing a federal lawsuit, accusing McDonald’s of trademark infringement and unfair competition. The company argued that McDonald’s had copied not only the idea of a bundled kids’ meal, but its exact format, marketing structure, and even its packaging concept, with slightly different cartoons.

The late ‘70s were a time when consumer advocates, right or wrong, were looking for a chance to strike a blow against corporate power. Legal experts viewed the case as a rare and important challenge by a smaller innovator against a corporate giant. But….wait. Burger Chef had failed to formally trademark or patent key elements of the Fun Meal. The court ultimately dismissed the case, ruling that the concept of bundling food with toys in child-oriented packaging was too broad to be protected as intellectual property. (Besides, Cracker Jack wants a word…)

As Elpack.co.uk reports: “The lawsuit was ultimately dismissed… The idea of bundling food with toys and child-themed packaging was deemed too generic to merit legal protection.” The courts found no legal wrongdoing. But the ruling was a devastating blow for Burger Chef.

Already struggling with corporate mismanagement, over-expansion, and competition from McDonald’s selling Happy Meals, Burger Chef never recovered. In 1982, General Foods sold the brand to Imasco, the Canadian parent of Hardee’s. Most Burger Chef locations were converted to Hardee’s stores or shuttered entirely. By 1996, the last Burger Chef closed its doors.

The Nature of Capitalist Innovation — Imitation and Improvement

So, who invented the Happy Meal? And does it matter?

Yolanda Fernández de Cofiño really did have a good idea, adapting a children’s menu for Guatemalan families. More people bought meals as a result, a lot more. But Burger Chef really did conceive and produce a whimsical, folded box Fun Meal with cartoons and puzzles printed on the box, and with child-sized portions, and it was fully in operation across the US years earlier. On the other hand, McDonald’s marketing executive Bob Bernstein really did gather together the pieces, and took a huge gamble on marketing the Happy Meal, going all in on the concept, the packaging, and the (new) cartoon characters, combining the parts into a nationally scalable product.

The answer is that it doesn’t really matter now, though of course it mattered to the participants at the time. The complexity of innovation, and the ability to adopt and adapt innovations we see around us, is the real essence of creative destruction. McDonald’s did not destroy Burger Chef; that was the logic of profit and loss. But the innovations Burger Chef brought to the market changed the business in ways that now seem essential: all of us younger than about 60 remember Happy Meals at McDonald’s as a rite of childhood.

Rather than undermining the validity of the Happy Meal’s story, this multiplicity highlights something crucial about how capitalist innovation works. In a market system, ideas are rarely born perfect and complete. Rather, parts are borrowed, copied, improved, and scaled. Success does not always go to the first inventor, but often to the best replicator and popularizer. James Watt didn’t invent the steam engine, but he produced steam engines that were commercially viable.

As Katarina Hall rightly notes, Fernández de Cofiño’s contribution “is a testament to Guatemala’s deep entrepreneurial energy — an informal, voluntary spirit that thrives even in the face of bureaucracy and poverty.” Her story shows how powerful innovation can emerge from ground-level observation, not corporate strategy.

Likewise, Burger Chef’s experience reveals the fragility of innovation when not legally protected or effectively promoted by competent management. Frankly, it’s not clear that Burger Chef should have been able to patent the concepts it innovated, and McDonald’s did not directly infringe on any trademarks, since they used new and different cartoon characters.

So the conclusion should not be colonialism, or cynicism; creative destruction requires realism. Capitalist economies work because good ideas move, spreading quickly. Innovations get copied, improved, and recombined in unexpected ways. The Happy Meal wasn’t “stolen” so much as refined. It emerged from a decentralized ecosystem of franchise owners, regional ad firms, and small competitors.

In the end, the Happy Meal is not just a fast-food product — it’s a case study in how markets generate progress. Imperfectly. Inequitably. But effectively.

Burger Chef is long bankrupt, the end point of the “destruction” of capitalism. Yolanda Fernández de Cofiño is also gone; she passed away in 2021. Yet their ideas are still served millions of times each day — in red boxes, with golden arches. And with a toy.